The Apple Merchant of Babylon 2

Begin at the Beginning

🍎

Golden Calves, Apple Tarts, & Klepto Snakes

At the back of Shesha’s store customers could find images of gods and heavenly nymphs in complete abandon. Beneath them were the graven images of local flood-plain girls, each promising to adopt the names and postures of their Indian ‘love gurus.’ Customers paid two shekels to lift the light blue curtain at the back of the shop.

One wandering Hindu, called Tantruman, was incensed at the blatant use of his religion for commercial uses. But then he thought of the lust of the gods, and how the worldly was but a facet of the divine. He thought about how divine the worldly figures were, and how it was all an illusion anyway. Determined to penetrate the mystery of the soul embedded deep within the flesh, he too lifted the blue curtain, and found himself lost behind the veil, deep in the snaky back corridors of Shesha's shop.

The situation had gone from healthy competition to whorehouse debauchery. Cartloads of apples came from the east, cartloads of Phoenician whores from the west. The city was awash in cut-rate bargains and back-room deals, shiny rosy surfaces, golden calves, and moon-shaped bite marks. Soon, no one cared about the economic or religious issues anymore.

Moe was desperate. He took one of the plump Kashmiri apples and threw it against the wall. It splattered open, and fell to the earth in juicy pieces. From out of the pulp crawled a grey worm. He sat there, thinking.

He got out a fresh clay slab and a sharp new stylus, and began at the beginning:

Once upon a time there lived a man and a woman in a Garden. Every day they would eat of a beautiful apple tree that belonged to the One True God. The tree was an Assyrian tree, situated only a stone's throw from the suburbs of Babylon. Its branches were a luminous green and its apples were always ripe and juicy. The apples from this tree were far tastier than the apples from the decadent valleys of the eastern demons.

The man and woman lived in perfect harmony until one day an evil serpent called Shesha slithered across the dry and burning soil of Elam. Reaching the blessed green fields and orchards on the outskirts of Babylon, the serpent slithered up the trunk of the tree…

Moe always thought he had the makings of a great story-teller. He wondered if he might even expand his apple-tree vignette into a larger story, perhaps one day into a famous epic.

But how could he rival the ever-popular Gilgamesh, with its account of the wrath of the gods, the Flood, and the evil Serpent in the pool who stole the plant of immortality? Yet he’d always wondered, What was the snake doing down in that pool anyway? How did he smell the plant? How did he manage to snatch it away from Gilgamesh? (You'd think that Gilgamesh, so renowned in battle and wisdom, would've guarded it a little more carefully!) And why, once the Serpent committed this theft, did he slough off his skin? What did he do with the plant afterwards? Why wasn't he apprehended, and punished by the gods? The story was crying for a sequel.

🍎

The Saga of Shamash

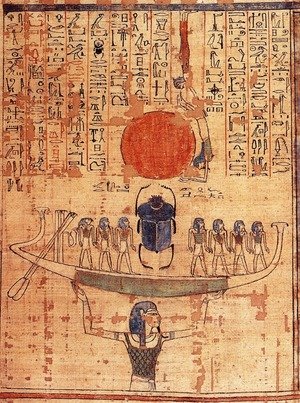

And how could any story of his ever compete with the greatest story of them all, the 5000 year-old Saga of Shamash, Deity of the Sun? The Saga was the greatest piece of writing of all time. It started with the fall of the Sun God into this world: into the temples with their money-dealers and prostitutes, and into the council chambers with their vampires and their ten-headed snakes. It then described the Sun God's miracles, such as walking on water and bringing back to life the morality of a corrupt market official. It also included a moving courtroom scene where Shamash challenged the tyrant Enlil and the monster Humbaba, just as two thousand years later Shamash would challenge the decadent priests of Uruk. The Saga concluded with the Sun God's defeat of the monster Chaos and with His ascent back into the skies.

No one had to be told why Shamash was later seated at the top of the Code of Hammurabi; it was obvious from reading The Saga. And who hadn't read it?

If Moe could ground his story in references to Gilgamesh and The Great Saga, then the artistic truth of his narrative would have a pedigree that no one could doubt. It's true, he worried, history is long. Perhaps one day people wouldn't remember all the details of The Great Work itself. Yet even as he thought this, he thought, What rubbish! Of course they’ll remember!

Moe didn't believe for a second the bizarre prophesy made in the final (and perhaps apocryphal) chapter of The Great Work. In this chapter, Twilight of the God, the anonymous author prophesies that 3600 years after the founding of Ur the two great epics would be eclipsed: Shamash and Gilgamesh would enter occultation, hidden from the eyes of men. The prophecy also asserted that Gilgamesh would reappear 2,200 years later, and that the Great Work would reappear two hundred years after that. What a bunch of baloney, Moe thought. The numbers are just made up. And what idiot imagines he can read the future?

Moe decided to make the greatest compliment one writer can make to another. He would take elements from the Great Story, swapping Shamash for the One True God, and rewrite the ending while he was at it. Instead of Shamash rising into the skies (and leaving everyone on earth literally sinking into the mud of the Euphrates, and metaphorically sinking into the mud of their own uncertainties), his One True God would hover over the earth. He would hover long enough to tell people the answers to all those unanswered questions about the snake, the secret of immortality, and how Shamash parted the waters on his way out of Africa.

Moe could add some laws like those of Hammurabi, and also some practical information: when to take a day off, what types of animals to eat, etc., the sort of thing that would show to people that his One True God gave a damn about their lives. He wasn't afraid to get his hands dirty, to meddle like a good Father in the lives of his children. It'd also create a dramatic contrast. Just imagine the Lord of all Space and Time talking to that scared young immigrant girl Ruti in her dusty corn-field. Or to Braham the butcher, just as he's about to bring his blade down onto the neck of a ceremonial calf.

In his story, the One True God would raise the stakes. He would make His moral points so powerfully that humans couldn't help but pay attention. This might even save them from themselves. But how to write this story so that they would get into the habit of making abstract moral commitments, like the one his fellow merchants ought to make to keep the foreign merchants out? How to make them afraid to break a deal? How to make them understand that if they broke a deal, their tents would burn and the fire of God would incinerate their storage bins?

🍎

Author! Author!

Then Moe had a vision: in the wide volume of his brain he saw a reworking of the old stories, grouped into one epic, and bound together with leather straps in a bin three cubits long. The Holy Bin!

Once Moe's vision faded, he realized how big the task was. How on earth could he get people to read about his God and forget about the adventures of Shamash? For there he was, on every market stall and street corner: the bright god who fired up Gilgamesh to defeat the monster Humbaba, and who dispensed justice at the highest level. The god the merchants came whining to whenever they wanted other people to treat them honestly.

The Saga was so famous that most of the time, people didn't even write The Saga. They just wrote in the story or in the text. Moe was sure there would never be a time when grandmothers didn't recite its sacred verses to their sleepy grandchildren around the family hearth. He was sure that even in another five thousand years from now schoolchildren would sing its merry poems while playing hopscotch in the dusty street. And philosophers would brood on its deeper passages — and like all Mesopotamian stories, this one had passages so dark that people were afraid to read them after the sun went down. Moe picked up his stylus and inscribed a poem he called, “The Cup of Life.”

The old men brooded all day

on the cup of life, and on its weedy dregs,

thinking of the inexplicability of everything,

as they watched the boats passing oceanward

along the dark waters of the Euphrates,

to be met in the end,

at the bottom,

by Ereshkigal,

serpent-laden Goddess of the Deep.

Was it possible to make people forget about those gods and all their dark dealings? And about all the dark nothingness of their endings?

🍎

A Better Way

If only he could replace the lawless deals and politicking of the gods with something else. If only he could substitute their grim visions of being battered by the wayward forces of the universe, with a vision of a loving God, one who was always in control, and one who made it clear what he expected from the human race. One who, once double-dealt, would smite his enemies like so many apple-merchants from Kashmir! Like so many homosexuals from Sidamu and Emar! What his people needed was a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist: one angry God with family values against one foreign Devil who lusted after nothing but wine and Hindu porn.

His story might also give his family a much-needed direction. Ever since the iron, apples, and foreign peoples poured across the frontiers, Moe worried that his family was starting to lose its way. It arrived from southern Egypt, landing in Ur decades ago, and made its way to Babylon, which he called home. Yet in many ways his people had always wandered. His father’s mother said that her family came from the Caspian Sea, and before that India, and before that the Yellow River of the Far East. But the wandering wasn't just literal: his people were also starting to wander in their allegiances, drifting toward the beliefs of the Babylonian masses. In brief, they were starting to assimilate.

🍎

Alternatives on Offer

Some of his people were even lending their ears to the wandering sadhus, who told them that they would be reborn in a colourful paradise or in a wonderful mansion, if only they did puja to Lord Shiva. The next world would be like this one (they would get to fish and hunt again; they would get to drink and have sex, and listen to the old stories), only it would be even better.

Their desire to believe in a different afterlife was understandable. His One True God only offered some vague underground existence, or at the best some vague Garden or World to Come. But this vague destination lacked everything people had come to enjoy in their lives. It was true that his One True God's afterlife was slightly better than what was on offer around them. In Gilgamesh the soul flits like a broken bird in the dust, and the great warrior Enkidu has a dream of the afterlife, in which he gets dragged by a terrifying bird-man into the dark chambers of Ereshkigal, Queen of Darkness. It was all so unendingly grim!

Not that it didn’t have its enticing bits: The one most people liked (because of the sleazy cabaret aspect, Moe suspected) was the story about Ishtar descending to the underworld to ask for the return of her lover Tammuz. At each gate she passes, she drops one piece of her clothing. Cloak, lingerie, drop piece by piece as she got closer, lower, darker down in the torchlight gloom to arrive at the feet of Ereshkigal.

But of course, Ishtar doesn't get what she asks for. No one seemed to.

In yet another grim vision, Gilgamesh makes an arduous journey to a faraway garden of eternal life. Yet when he finally gets there he's told that no one else will be allowed to travel to this happy place.

The grimmest vision of all involves the boat of Magilum. At the end of life, everyone gets on this boat, which then drifts onto the river and sinks. Slowly, inexorably, fatefully (all the words that suggest the futility of it all), the water creeps to the knees, the hips, the chin, until a few frail hairs drift in the current that sweeps everything away. Moe could imagine the look on the faces of the travellers as the water spilled over the gunwale.

🍎

Final Judgments

It seemed to Moe that the grim Babylonian stories about the afterlife couldn't compete with the stories coming from Egypt. Who would choose to believe in watery death — the boat of Magilum slowly sinking into the deep waters of the Euphrates — when you could skim over those same waters? Who wouldn't swap the Euphrates for the Nile? Who wouldn't give their eye teeth to roam the marshes with Nebamun and his flock of blue-grey birds?

Moe admired the Egyptian priests. They gave their subjects something to believe in: a final journey and a chance to live forever.

Moe felt that people had a right to stand at last in front of their gods. He felt they should be granted a final judgment, instead of being tossed into the Euphrates or thrown helter-skelter into the dusty realms of the frightening Ereshkigal. Given a choice, who would choose to remain forever at the whim of indifferent gods and nebulous underworld forces? Who would choose to believe that life had no intrinsic meaning, and that at the end of it all one fell back into inanimate chaos?

Moe remembered a madman he once heard raving on the other side of the market. The man’s name was Danny, and he had scrawled in hieratic script the words he screamed between the fruit sellers and the hat vendors: “Many of those now sleeping in the dust of the earth will awake. Some will awake to eternal life, but others to reproaches and to everlasting doom!” What a brilliant idea!, Moe thought. Profit motive and loss aversion all rolled into one! But would his people ever believe it?

If there was a final judgment, it had to be just, like the judgment of the great sun god Shamash. And it had to supply meaning to peoples’ lives. It had to make sense of the sacrifices they made and the good deeds they performed during their earthly years. If they led evil lives, they’d be annihilated by fire, or dance on brimstone until they admitted that they sold black market apples or mixed business with forbidden pleasure. Or maybe they were just obliterated, like a puff of smoke, thus denying them the only thing that was ever precious to them: their own lives. But if they lived a decent life, they got to remain forever in some lush gardens of the Nile, or travel across the heavens with Ra on his fiery course. Or with Shamash across the Euphrates, what did it matter? And they got to have sex with beautiful young women, Deepika or Eveline, it was their choice. (But men couldn’t sleep with other men, even in the afterlife. That was just plain wrong.) In brief, they got whatever they wanted in life but were too disciplined, too decent to take.

This Egyptian option was a great lure for people to be good, and for people to feel that how they acted in life mattered. Not just in general or in abstract principle, but also in their own personal fates. It all came down, as usual, to self-interest.

This possibility however raised another problem: how could his people know whether one version of the afterlife was true, and another false? How could they distinguish between the unprovable claims of one god and the unprovable claims of the next? What, apart from self-interest, would make them choose the glorious afterlife of Ra over the grim afterlife of Shamash?

🍎

One God to Rule Them All

The one advantage his religious system had over all the others was that in his system there were no other options. Let people debate which god triumphed over which other god. In his religion there was no battle because there were no claimants to the throne. Let them scratch their heads over the puzzling genealogies, the bastards and the demigods. In his religion there was no genealogy because there was no father and there was no son.

How could he possibly explain all of this to his people? How was he going to make them forget about gods that no one had ever seen yet which took every possible form and were characters in all sorts of dramas?

How was he going to make them believe in his God who also couldn't be seen, yet in addition (or subtraction!) couldn't be depicted in any form whatsoever?

🍎

He Is What He Is

Moe realized he couldn’t possibly define the nebulous conception of Deity he had in mind. He decided therefore to make his God so contradictory — sometimes kind and sometimes bloodthirsty, sometimes merciful and sometimes genocidal — that people could only conclude that any conception of God was absolutely and forever impossible. Like Nature or Fate.

His good friend Aziz, with whom he drank many a cup of celestial wine at The Persian Tavern, understood this point very well. Aziz even suggested that there was no point trying to engrave the names of God into clay. There were too many of them. And all of them weren't nearly as true as the feeling he got in the pit of his stomach when he peered into the bottom of his empty cup.

Aziz asked Moe, “Why not just say, God is what God is? I mean, you can get all poetic about roses and cosmic Love. But about God, what can we really say except that He is what He is?”

Aziz added, “I’m not even sure we can say that. Can we really say that God has a beard?”

In defining God, Moe realized the enormity of the task he had set for himself. For how could he define something that he could never see, and at whose attributes he could only guess? But how could his people worship a God if they didn’t have even the slightest concept of who or what He was?

🍎

He Did What He Did

His people needed explanations. They had a right to know where their invisible, omnipotent, eternal Deity came from. Yet the more he thought about it, the more it seemed a never-ending puzzle. Everything he imagined might be a beginning seemed to have some earlier thing that caused it. How did the One True God get there in the first place? What was the ultimate cause? Did He create Something out of Nothing, or More Things out of Something? Perhaps it would just be better to say He did what He did, and leave it at that.

Moe picked up a blank slab. He began this time with a statement that no one could get wrong: In the beginning God said, Let there be Life!