Gospel & Universe 🍎 The Apple Merchant of Babylon

Final Judgments

Swapping the Euphrates for the Nile - One God to Rule Them All

🍎

Swapping the Euphrates for the Nile

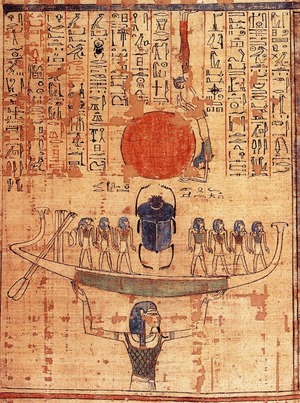

It seemed to Moe that the grim Babylonian stories about the afterlife couldn't compete with the stories coming from Egypt. Who would choose to believe in watery death — the boat of Magilum slowly sinking into the deep waters of the Euphrates — when you could skim over those same waters? Who wouldn't swap the Euphrates for the Nile? Who wouldn't give their eye teeth to roam the marshes with Nebamun and his flock of blue-grey birds?

Moe admired the Egyptian priests. They gave their subjects something to believe in: a final journey and a chance to live forever.

Moe felt that people had a right to stand at last in front of their gods. He felt they should be granted a final judgment, instead of being tossed into the Euphrates or thrown helter-skelter into the dusty realms of the frightening Ereshkigal. Given a choice, who would choose to remain forever at the whim of indifferent gods and nebulous underworld forces? Who would choose to believe that life had no intrinsic meaning, and that at the end of it all one fell back into inanimate chaos?

Moe remembered a madman he once heard raving on the other side of the market. The man’s name was Danny, and he had scrawled in hieratic script the words he screamed between the fruit sellers and the hat vendors: “Many of those now sleeping in the dust of the earth will awake. Some will awake to eternal life, but others to reproaches and to everlasting doom!” What a brilliant idea!, Moe thought. Profit motive and loss aversion all rolled into one! But would his people ever believe it?

If there was a final judgment, it had to be just, like the judgment of the great sun god Shamash. And it had to supply meaning to peoples’ lives. It had to make sense of the sacrifices they made and the good deeds they performed during their earthly years. If they led evil lives, they’d be annihilated by fire, or dance on brimstone until they admitted that they sold black market apples or mixed business with forbidden pleasure. Or maybe they were just obliterated, like a puff of smoke, thus denying them the only thing that was ever precious to them: their own lives. But if they lived a decent life, they got to remain forever in some lush gardens of the Nile, or travel across the heavens with Ra on his fiery course. Or with Shamash across the Euphrates, what did it matter? And they got to have sex with beautiful young women, Deepika or Eveline, it was their choice. (But men couldn’t sleep with other men, even in the afterlife. That was just plain wrong.) In brief, they got whatever they wanted in life but were too disciplined, too decent to take.

This Egyptian option was a great lure for people to be good, and for people to feel that how they acted in life mattered. Not just in general or in abstract principle, but also in their own personal fates. It all came down, as usual, to self-interest.

This possibility however raised another problem: how could his people know whether one version of the afterlife was true, and another false? How could they distinguish between the unprovable claims of one god and the unprovable claims of the next? What, apart from self-interest, would make them choose the glorious afterlife of Ra over the grim afterlife of Shamash?

🍎

One God to Rule Them All

The one advantage his religious system had over all the others was that in his system there were no other options. Let people debate which god triumphed over which other god. In his religion there was no battle because there were no claimants to the throne. Let them scratch their heads over the puzzling genealogies, the bastards and the demigods. In his religion there was no genealogy because there was no father and there was no son.

How could he possibly explain all of this to his people? How was he going to make them forget about gods that no one had ever seen yet which took every possible form and were characters in all sorts of dramas?

How was he going to make them believe in his God who also couldn't be seen, yet in addition (or subtraction!) couldn't be depicted in any form whatsoever?

🍎