The Double Refuge ✝︎ Saint Francis

Believe it or Else

Threats - Metaphor & Dogma

✝︎

Threats

Medieval Christianity insisted on one anthropomorphic definition of God and on one path to this God. History on the other hand tells us that there are many gods, many versions of God, and many paths.

Even if there's only one God, it doesn't follow that we must bend our knee in any particular fashion. Everything we've been told about It, and every reason we've been given to fear It, is soaked in myth and historical contingency. One could well believe in a God without believing that It 1) dons a beard, 2) speaks in Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, or Sanskrit, 3) has written down its plan for humanity on tablets or paper, or 4) will incinerate anyone who doubts Its existence or questions the manner in which others depict Its existence. If there's a God, It may well prefer to be defined openly. Or not at all.

In the Medieval period, Christians claimed a monopoly on the Grand Plan of the universe, and added the following threat: Believe It or else! Even today there hovers over Christianity a remnant of this crude Medieval dogma: if you doubt the capitalized Mysteries of the Bible, and look for meaning in the uncapitalized mysteries of the universe around you, you are informed, one way or another, that you are dooming your soul.

One can see how early Christians misunderstood our place in the universe and why they chose faith and religion over reason and science. There was, until the 20th Century, no verifiable astronomy, geology, evolutionary theory, neurology, or genetics to explain -- or define the difference between knowledge and speculation about -- anything from the stars to the human body. It was easier for believers to integrate Aristotle with religion than to push his method of observation toward more scientific conclusions. Also, the amplitude of violent human behaviour and catastrophic events was so great (wars, inquisitions, plagues, etc.) that it was helpful to believe in Heaven for good people and Hell for rapists and murderers, especially in the absence of a modern system of justice or anything that resembled modern democracy or human rights.

Yet it isn’t so easy to account for the Medieval conviction about God and the human spirit. Why did Christians think they had unique insight into the deepest corners of the soul and into the deepest operations of the universe? And why did they define their speculations in terms of hellfire dogma rather than doubt, open enquiry, compassion, respect, love, beauty, and truth, especially since many of these were preached by their own revered Jesus? Why did they decide that anyone who disagreed with them was not simply wrong, but was also evil, and therefore doomed to the fires of Hell?

Many Christians have rejected the cruel exclusivity of the Medieval Church, yet many traditional Christians still think that if you don’t believe exclusively in Jesus, you're fundamentally wrong, inferior, or doomed; you either lack a true spirit or this spirit's deficient and corrupt. If you don’t believe exclusively in Jesus then your spirit can’t be loved by God. Whatever you do, your spirit doesn't match the first class spirit of the believer. As a result, you'll spend the rest of eternity in Hell, invaded by a hollow nothingness or tortured by fire and black devils with pitchforks.

How is it possible to square this type of thinking with ideals of love, justice, or equality? If one must discard love, justice, and equality for the sake of this type of dogma, what can this type of dogma be worth?

While Hindus, Buddhists, and Daoists have their own elitisms, prejudices, and irrational forms of belief, they at least don't condemn to eternal fire those who don't share their beliefs. Not that the bad Hindu, Buddhist, or Daoist can’t take a long tortuous journey through dark worlds, or visit some sort of sexualized pandemonium after they die…

Eastern religions contain Hells and depict monsters torturing malevolent souls, from the obvious hell of Boiling Excrement to the vague yet ominous Single Copper Cauldron — as in these versions of Hell from Burma and Thailand:

Yet Hindu and Buddhist hells are different from the Christian Hell for at least two reasons. First, Naraka (Hell) in Hinduism and Buddhism is temporary, not permanent. In this sense there's more possibility for redemption than in the traditional Christian Hell. As a result, one might call Naraka a Purgatory rather than a Hell. Second, while Hell is likewise used to scare people, it's the effect of a cause, not the effect of a belief. You don't go to Hell because you hold a particular conception of God or the universe. You go to Hell (until you burn off your bad karma) because you raped or murdered, stole food from a starving family, bribed and coerced your way through life, or committed some other nasty act. If you commit evil actions (bad karma) then you'll enter a punishing afterlife or incarnation (bad samsara). This basic principle of justice crops up again and again in the Bible (Job 4:8, Proverbs 22:8, Jeremiah 17:10, Luke 6:38, Galatians 6:7, 2 Corinthians 9:6) and is summed up beautifully in the phrase, As ye sow so shall ye reap. The phrase isn't As ye believe so shall ye reap. It's a pity that the early Church didn't make salvation a function of action rather than belief.

It’s a pity that while ideas surrounding the afterlife were various and changing, the early Church didn’t 1. allow a variety of beliefs and 2. put an emphasis on the universal standard of action. One has to remember that in the Classical Age the exact nature of Hell was far from set in stone. In most of the Old Testament Sheol is a vague afterlife realm, similar to that of the Mesopotamians and early Greeks. No matter what one believed, there was barely a glimmer of hope. Over time, this view of Hell appears to morph, taking on something of the Tartarus/Elysium dichotomy of the Greeks, and offering something of the Paradise found in Egypt and Persia. In such a changing scenario, the early Church could have made salvation a place accessible to whoever lived a decent life, regardless of their beliefs in One God, three Gods in One, a million gods, or 777 gods coalesced into One. Unfortunately, they rejected thinkers like Origen, who argued for belief in Jesus but also for a wide scope of redemption, perhaps even allowing Satan to be redeemed. Thus the early Church paved a narrow path to the Gardens of Paradise and a wide path to the bonfires of Hell.

What does it mean, anyway, that God will cast into flames those who believe in reason and science and not in revelation and religion? What we mean by reason and science didn't exist in the Classical and Medieval Ages, which were the time periods during which the hellfire doctrines were established. There was no scientific method and no body of scientific knowledge to explain the world: no laws of physics to hold the Earth in its orbit; no evolutionary model to show where our bodies come from; no DNA to explain how the complex chemistry of the body works. There were no good telescopes or microscopes to even start the conversation in the right direction. The Medieval priest who condemned the vain philosopher to eternal fires couldn't have been referring to today’s scientist or agnostic because such a person simply didn't exist. Perhaps if Christ were around today, he would find a job at the ALMA observatory high above the Atacama Desert.

I'm particularly fond of this observatory, both for what it's doing to advance astronomy and for its name: the Atacama Large Millimetre Array. The acronym ALMA means soul in Spanish. That a scientific observatory may be the home of soul might seem an irony. Yet from an agnostic perspective, it's a paradoxical possibility.

✝︎

Metaphor & Dogma

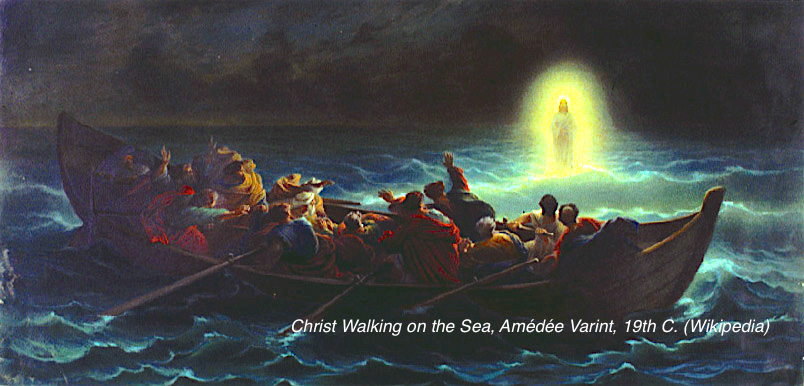

Because the early and Medieval Church set the terms for dogma in the West, and because their dogma continues to be supported by a complex, hallowed exegesis, many people today are ill-equipped to challenge it intellectually or to replace it with a viable alternative. Even when people explore alternatives, the old dogma can work deeply on the psyche. It can insinuate that what appears to be a metaphor is, mysteriously, the literal truth. A metaphor equates two things that are similar but aren’t the same, with the understanding that there’s an implied comparison. This is different from a simile, in which the comparison's overt. The Church, unfortunately, convinced people that similes didn’t lie beneath their metaphors. They convinced people that like or as wasn't implied when they equated two things. What might have been framed as an overt comparison — Communing with God is like drinking wine — was instead framed as a metaphor that they then claimed to be a literal and miraculous Truth: You’re drinking the blood of Jesus. In other words they ignored the function of metaphor completely, and instead forced congregants to agree to a literal phrasing that contradicts everything they know about time and space. How are rational, practical people supposed to literally understand the phrase, Jesus walked on water?

In describing possible afterlives, they created vivid pictures of Heaven and Hell and then tried to make people believe these imaginary pictures were real places. The problem is that because we can’t be sure about the afterlife, we can’t be absolutely sure that these places don't exist. Even if we’re intent on a rational, metaphorical interpretation of Heaven and Hell, the emotions (especially if we were indoctrinated as children) capitalize the concepts and turn them into real places in our imaginations.

And then comes the inevitable threat: Believe it or else! Our minds understand the manipulation, yet our emotions conjure puffy clouds and plains of fire. Perhaps this is because these ideas are deeply embedded between our feelings and our thoughts, and between our thoughts and our inherited vocabulary — the vocabulary that's defined our place in the universe for over a thousand years. Even the simplest words and phrases, such as forgiveness, guilt, fire, water, blood, grace, wicked, judgment, spirit, godless, saved, angelic, lost, good, evil, meet your Maker, damned if I know, heaven knows, go to hell, God knows, sure as hell, are rife with fifteen centuries of Christian meaning.

✝︎

Next: ✝︎ Pascal’s Wager