Gospel & Universe ✝︎ Saint Francis

The Baby and the Bathwater

The Bath Water - Negatives - Positives

✝︎

The Bath Water

Political cartoon by Chris Riddell, for The Observer

For over a thousand years the Church told its account as if it were fact. The Church insisted that the universe was created by a monotheistic God and that we must believe in the Son of this God. We must believe in the big M Miracles and Mysteries of the Creation that took place in a week, the water that turned into wine, the Virgin who gave birth, the flying body that was once dead, the rebirth that only Jesus can provide, etc. We were told to look down on the small m mysteries of the world around us. We were told to listen to the priests but not to the free thinkers, agnostics, doubters, pagans, scientists, or to any of the other ‘vain philosophers.’ The Church countenanced cruelty and barbarism by saying that the ends -- keeping the Faith pure -- justified the means: burning books, torturing heretics, and suppressing free inquiry. One could say that many Christians during the Middle Ages sacrificed freedom and justice to make a fetish of their Belief.

One could object that there was no other plausible Belief System on offer -- certainly no scientific Belief System. This is the point I make in Summa Post Theologica.

Yet the paucity of options is no excuse to exclude the free exploration of options. Not only did the early Medieval Church do all it could to crush Ancient and Classical systems of epistemology (or meaning) that disagreed with Christianity; the late Medieval Church did its best to pre-empt an overarching Modern scientific explanation. This is perhaps best illustrated in a literal and figurative take on the word overarching: the Church conflated astronomy (our understanding of the world and its place in the overarching sky above us) and theology (our understanding of the human spirit and its place in God's overarching Plan for the universe). In the process, the Church wrongly asserting that it had the Answer to the secrets of the universe itself.

Yet the Church also supported charities and founded universities. It promoted a version of Humanism that helped shape the Modern world. In the 12th century Thomas Aquinas wrote that reason and nature work hand in hand to uncover the glory of God’s universe. In the 16th century, Christians from Wittenberg to Glasgow protested against the monopoly of Rome and started to interpret the Bible for themselves. This Protestant Revolution was a curious precursor to secularism: Protestants wanted the freedom to believe in their particular dissenting religious view, and therefore created (intentionally or not) the social and political environment in which people were free to hold any dissenting religious view. Christian perspectives exploded in every direction: Baptists, Anabaptists, Mormons, the Clockmaker God of the Deists, the social activism of the Jesuits, the leap of faith of Christian existentialists, the political rebellion of the liberation theologians, etc. By the 20th century, many Christians were far from doctrinaire.

Traditional and conservative Christians today condemn the abuses of the Inquisition and applaud the scholarly and creative activity of the late Medieval and early Modern periods. Yet many haven’t condemned the dogma that lay behind Medieval Christianity and its Inquisition: they still think that their Truth is higher than all other truths. They still tell their children that they must believe in Creationism, in Moses and his Ten Commandments, and most of all in Jesus and all the Miraculous things he did. If their children don't believe in the Christian Scheme of Things, God will punish them. They may even spend eternity burning, with pins in their eyes, or wading through a swamp of serpents, or wandering through an empty vacuum of nothingness, etc.

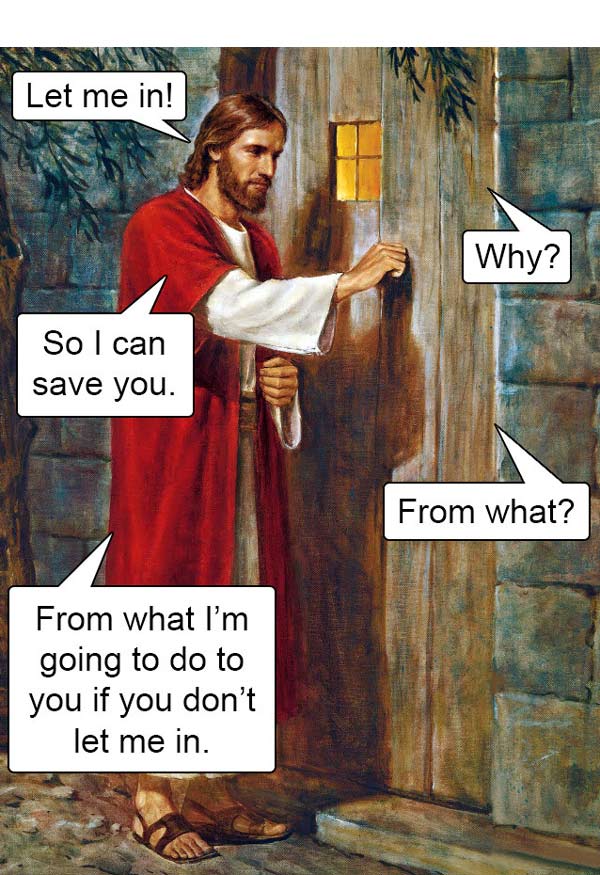

The following image (doctored by the insertion of dialogue, by a source I can't confirm) gets succinctly at a contradiction that still haunts Modern Christianity: the use of threat and punishment to promote love and forgiveness:

Jesus at the Door by Del Parson (dialogue not included in the original)

This crude threat is accompanied by other Medieval ideas: to reach Ultimate Truth you must be a Christian; Christians are a special group of people who exist on a higher spiritual Plane; to be a Christian you must believe in Creationism and in Miracles such as a Virgin giving birth, a Man walking on water, water turning to wine, a body flying up into the sky, this same body returning in the future, and a Heaven admitting only people who believe in the aforementioned Miracles. Other dogmatic strains of thinking (such as males are better than females, heterosexuals are better than homosexuals, etc.) make many Christians wince, yet they're told they must accept these if they're to be worthy of God's love.

Christianity has also been packaged so that one can't approach it historically or scientifically. People are told that they can't retain Christ's spirit of love, truth, forgiveness, sacrifice, humility, etc. without accepting spurious chronological references as well as Miracles that are impossible for rational, practical people to believe.

Medieval belief in Miracles and salvation only for the elect isn't the same as belief in a benign Force that governs the universe (God), or in a figure who expounded the ideals of love, forgiveness, and fearless honesty (Christ). By insisting on Miracles and the elitist notion that only those who believe in these miracles will be saved, dogmatic Christians do at least three harmful things: 1) they make it impossible for reasonable people to believe in or identify with what they say; 2) their notion of the Saved or the Elect deeply divides them from everyone who doesn't believe exactly what they believe; 3) their use of the threat of damnation coerces belief and creates antagonism in people who are categorized as hell-bound infidels.

One might object, Who cares? Isn’t it obvious that those who believe in Medieval dogma are throwbacks, doomed to sink beneath the weight of science, reason, Biblical scholarship, inter-religious studies, and the weight of the practical world? Why waste time arguing against dogma when there are more important issues?

I can think of at least four reasons why arguing against a dogmatic version of Christianity isn’t a waste of time.

✝︎

Negatives

1. Medieval dogma still has negative consequences.

For instance, many Christians still tell their children that evolution is only a theory, thus denying them the best explanation we have for life on earth. The Vatican has more or less accepted evolution, yet fundamentalist churches still carry on this tired debate. Many Christians coerce and traumatize their children by telling them that they'll go to Hell if they don’t believe in Jesus. Others insert metaphysical beliefs into issues (such as abortion or stem cell research) that are already hard enough to negotiate in practical terms. Some hold up the sanctity of life as a reason to ban voluntary assisted suicide, thus making it impossible (or at least illegal) to end a life that's in torment.

The Catholic Church still discourages birth control in countries where overpopulation's an enormous cause of suffering. The Church also hinders gender equality by insisting that a woman can’t become a priest or pope. Pope Francis is softening the Church's stand against gay marriage, yet his document of April 2016 suggests that not that much has changed: Every person, regardless of sexual orientation, ought to be respected in his or her dignity and treated with consideration... As for proposals to place unions between homosexual persons on the same level as marriage, there are absolutely no grounds for considering homosexual unions to be in any way similar or even remotely analogous to God's plan for marriage and family.

Fundamentalist Christians still balk at gay rights because of what they see as a Biblical injunction against homosexuality. While gender discrimination may be a result of cultural intolerance, this specific type of intolerance is encouraged by many conservative and fundamentalist churches. There are, of course, times when the opposite's true, for instance when the Western Anglican Church argued for a gender equality that African churches have yet to accept, or when Jesuits in South America fought against slavers on the behalf of the indigenous population. As I will explore below, Christianity has done, and continues to do, a great deal of good. Yet here I'm talking about keeping this good and throwing away the dogma that works against this good.

2. Many people are still frustrated by the psychological pressures exerted by dogmas they no longer believe.

If you’re exposed to dogma before you’re old enough to think things through (as I was in Sunday School and at a Christian camp) this dogma can remain deeply embedded in your mind and your emotions. This type of schooling seems to me a form of indoctrination or brainwashing, perhaps even a form of abuse. The effect is long lasting: it can create a deep gap (which is also a false dichotomy) between deep emotional experience and deep rational investigation. While dogma can eventually be replaced by the liberating experience afforded by agnosticism and doubt, the trauma is often so severe that the individual either relapses into the fold or revolts against all aspects of religion. Either way, it’s not easy dealing with a thousand years of religious dogma that you don’t agree with it. If Christianity got rid of the dogma and kept the love, sacrifice, community, good works, forgiveness, etc., this type of psychological turmoil could be mitigated, if not completely avoided.

3. Accepting dogma in Christianity makes it difficult to oppose dogma in other religions.

This applies to sensitivities (such as those of the brahmin who fears being polluted by an untouchable) and to actions (such as those of the jihadi who believes that strapping a bomb across his chest will get him into Heaven). If people can justify inequalities and cruel practices on religious grounds, they don't feel compelled to defend them on practical, realistic grounds. If we don't oppose Christian dogma, it seems only fair to keep our hands off other dogmas. If, on the other hand, we challenge our own dogmatic beliefs and practices, we have greater license to challenge those of Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Jews, Animists, Wikkans, etc.

4. The moral values of Christianity are greater than its vaunted miracles.

One can feel the love and power of God without accepting very specific and elitist notions of history and salvation. One can find deep meaning in love, charity, honesty, truthfulness, morality, compassion and forgiveness without believing that this can only come through one particular man who lived two thousand years ago. One can 'believe' in Jesus as an exemplar and deep inspiration without believing in magical stories about him, stories which are most likely just legend or myth.

✝︎

Positives

Here's a brief list of some of the valuable messages Christianity emphasizes, together with brief translations that highlight the universality, depth, and practicality of the messages:

— We're all sinners. No one's perfect. Christianity has for centuries confronted the reality of imperfection. But do we really need Augustine's doctrine of original sin to understand this reality?

— Confess your sins. Admit when you're wrong. The confession booth may be a great psychological relief, yet the notion that another person can absolve you of wrongdoing is morally suspect, and isn't accepted by Protestants in general. But the idea that we should admit when we're wrong is necessary psychologically and socially. It also allows those who have committed crimes to work themselves back into a moral life.

— Forgive others. Give people a second chance. Allow people to learn from their mistakes. In Shakespeare's play, King Lear says to Gloucester, through tattered clothes small vices do appear; robed and furred gowns hide all. All of us are flawed, all of us could use the benefit of the doubt. Our justice systems recognize this: if we admit that we've made a mistake, we're eligible for the forgiveness that allows us to carry on with our lives.

— Love your neighbour. The ideal of life is to care about others; to live in peace and harmony.

— Pray or meditate in order to improve and liberate yourself. Think about yourself and your actions within a larger moral context. Get out of yourself. Release your emotions and ideas from internal feedback loops, from what Sartre calls the nausea of seeing your own thoughts and emotions in everything. All religions have types of prayer or meditation that aim to free the mind and at the same time turn the mind toward a more ethical or constructive path. Taking time to dissolve sensory overload, confusion, disquiet, anger, and sadness allows the mind to get beyond its own patterns, its own self-centred responses, internal justifications, defensive thinking, traumas, and triggers. This isn't just a practical thing: the transcendence of self is also a defining feature of mysticism (communion with God and/or union with the universe).

— Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. This is democracy in a nutshell. What would the social contracts of Locke, Rousseau, or Mill be without the notion that the person standing beside you is as valuable as you are. This is such a wide and helpful concept that it earns its moniker, the golden rule. The inverse is also true: you can't be free if you mistreat others, or if you create or maintain a system in which a group of people is systematically better off than you or your group -- because of money, family, race, language, religion, gender, etc. Whosoever committeth sin is the servant of sin (John 8:34).

— Judge not, that ye be not judged (Matthew 7:1). Don't be quick to condemn others. He that is without sin among you, let him cast a first stone at her (John 8:7). As an adjunct to the golden rule, this urges people to understand the reasons others do things we may not like. It also suggests that we're subject to hypocrisy; that we tend to throw stones, forgetting that our own houses are made of glass. Shakespeare puts this passionately: Thou rascal beadle [official], hold thy bloody hand. Why dost thou lash that whore? Strip thine own back; thou hotly lusts to use her in that kind for which thou whipst her (King Lear 4.6).

— Don't kill, steal, cheat, etc. Such rules as we find in the ten commandments were in existence long before Moses, who's at best quasi-historical. The image of commandments written in stone brings to mind the clay tablets of cuneiform on which were written the legal codes of Ur-Namma (21st C. BC) and Hammurabi (18th C. BC). Most post-neolithic civilizations have variants of such practical laws to govern trade, property, the value of life, etc. Laws, like the other values above, can be maintained without dogma or miracles.

— Help others. Be charitable. The notion of service to others is so important that it is included in the powerful triumvirate of faith, hope, and charity. Even the guilt one is encouraged to feel can be helpful in motivating charity.

✝︎

Next: ✝︎ Keeping Baby