💙 The Blue-Eyed Sicilian, Part Three 💙

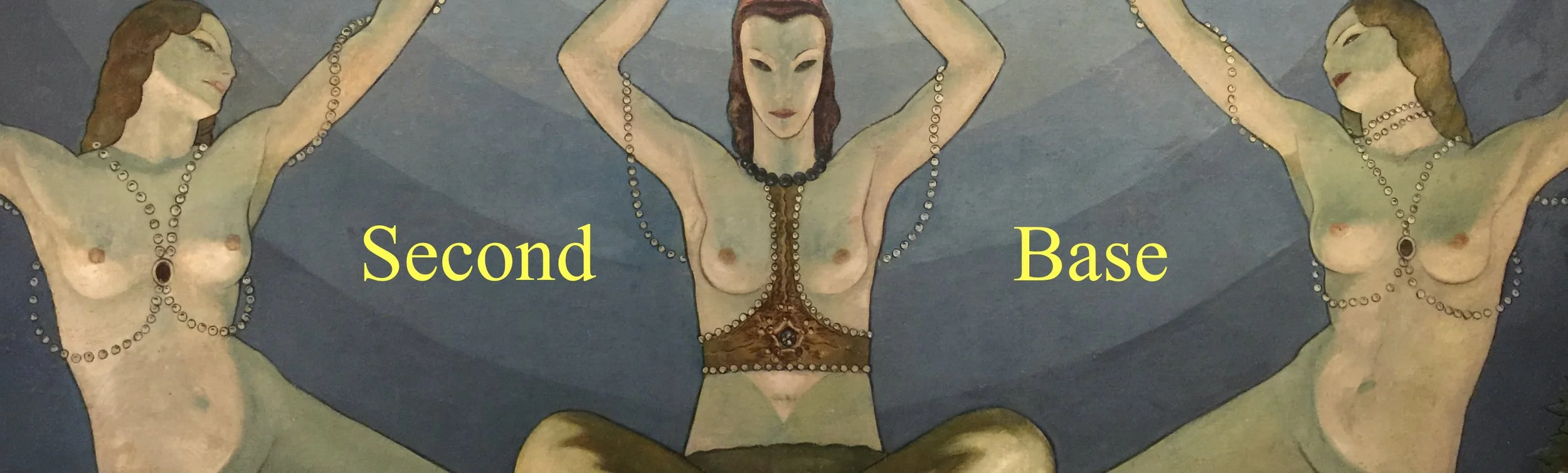

Second Base

The Roman holiday hadn’t gone quite like Tarnar had planned. It had in fact gone much better. He worried how Claudia would feel, just the two of them, sharing a two-room apartment a block from Campo de’ Fiori. As it turned out, she took it very well. The main evidence of this was that she was sitting calmly, with her legs in a lotus position on the couch. She looked up at him, appealingly.

They had just spent the morning walking around Piazza Navona and Piazza di Trevi, and were having a brief respite before lunch. Looking out the window, Tarnar saw the happy Italians talking with their hands and enjoying their thousand inside jokes.

A stone’s throw from Antiquity, they strolled into the 21st century as if they were time-travellers on a passeggiata to the stars. Yet they, like the other humans, had no idea what was coming next. Tarnar, on the other hand, had a great deal of information.

Tarnar turned around and took several steps toward the couch. He loomed over Claudia’s full figure, and her light golden skin. Her full lips were almost cherry red. Her eyes were looking up at him, deep blue and green, perfectly clear, almost crystal.

Her eyes reminded him of the fresh blues and greens of the Mediterranean, and of the Trevi Fountains, beneath the galloping horses.

Her eyes were like those of a model for an artist in the 14th century. They seemed to mirror the universe, to see past the clouds into the blue and golden realms of Heaven. They reminded Tarnar of Petrarch:

Gli occhi di ch’io parlai sí caldamente, / e le braccia, e le mani, e i piedi, e ‘l viso, / che m’avean sí da me stesso diviso, / e fatto singular da l’altra gente;

The eyes that I spoke of so warmly, / and the arms, the hands, the ankles, and the face / that left me so divided from myself, / made me different from all the others;

During their walk around the old town they’d been talking about myth and religion, and about the long march of time from the transformations of Ovid to the Assyriology of Adolf Leo Oppenheim. Tarnar continued his point, which sounded to Claudia a bit too much like a lecture: “Oppenheim was clear about the impossibility of truly understanding our past. If he’s right, the beliefs of the past can’t be absolute, can’t be relied upon. You’re right, Claudia: what they told you about God and Heaven was a beautiful myth. But the truth of the matter is that not everything outlandish is a myth. The truth of the matter is far more mythic, and far less beautiful.”

“But Clark, who can talk about truth? Wouldn’t that just be another myth?”

Tarnar turned away from her, stepped up to the window, and looked out onto the street. He saw the electricity lines, the crooked stones, the crude vehicles. Humans were stuck between worlds, with just enough knowledge to fool themselves. But why should Claudia, who deserved so much more, be kept in the dark? “I know, that’s the party line. Vain philosophy and all that. But to misquote Hamlet, there are more things in the open skies than are dreamt of in their philosophies.”

“But which skies are those? Are they the ones I see?”

“Yes and no. Yes, they’re the ones you see. There’s only one realm of skies, although the realm is more varied and more colourful than human astronomers know. Somewhere there’s a sky to match those colourful eyes of yours. The space between our fingers is infinitely small, and the space beyond the earth and the moon is infinitely large, but there’s no other dimension of space or sky, no fifth dimension, at least as far as we know. Forget Heaven and Hell, Nirvana and the Absolute, and all the other myths and stories. The only thing absolute is the relative. Your Einstein got that right.

“Your Einstein? Don’t you mean our Einstein? I know sometimes in English people say it that way. Like, your average Joe, no?”

“What colour are my eyes? What exactly do you think makes them different from yours?”

Claudia was taken aback. It wasn’t like Clark not to indulge her appetite for the quirks of the English language. Or was it, the average Joe?

She first started to notice the change in Clark last night. They were on the couch, and he whispered several bizarre expressions into her ear as he nibbled it. He also slid his hand up her blouse. He said, “I can’t get enough of your breasts! But God knows, there’s enough to go around!” She wondered, Around what?

Jokingly, he said something about second base, yet when he tried to explain the expression he slipped into some other form of speech which didn’t sound like English. Or Italian, Spanish, French, German, or Russian. The language was fricative with nasal sibilants. Perhaps it was Icelandic. Then he said impatiently that it was just an English expression, from baseball. But then he didn’t explain anything further. She understood baseball to be a form of cricket, which had more rules than Italian bureaucracy. She had heard people say That’s not cricket when somebody did something that broke one of the rules. But the only sports rules she knew about were football rules. Yet she also knew that in North America football was another game entirely.

She gave up trying to understand the metaphor. She decided to, as the English say, just let it slide, which also described more or less what he was doing with his hand beneath her blouse.

Because of the tension of the elastic, when he slid the bra up and around her left breast, the cup jumped upward. But because the elastic got caught on her nipple, it was unable to complete its long journey over the mound of her breast and up to her collar bone. This merely put pressure on her left breast, making it bulge and taut. Larger than ever. She could feel her breasts in the open air, and she saw him looking at them. She felt like Sophia Loren, with Marcello watching on.

This morning, sitting invitingly on the couch, she wanted to repeat that moment. Or take it further. But for some reason he kept talking about her eyes, like some fourteenth-century poet. Claudia wondered if this was an English form of foreplay. But this time his hands were nowhere near her breasts. His eyes weren’t even looking at them, for once. His gaze often flirted around her nipples, but this time he seemed to be after some other point.

He looked down at her feet, the toenails candy red. “I’m afraid I’m not, as you might say, completely normal. I’m not exactly even human.”

Now Claudia really didn’t know what kind of game he was playing. She guessed, however, that it was an intellectual game, and that the rules required references to literature and philosophy. “Ah, non ci credo. The intellectual is always thinking he is not the same as everyone else. The existential intellectual is even worse. Che peccato! Sartre saw the black root of the chestnut tree as if it were something from another planet. Or as if he was an alien. Was it a human garden in which he saw the black slithering root? Was it a cosmic snake, that root? Even the atheist seems to fall back into myth.” Claudia was quite pleased with herself, having woven together philosophy and English syntax without a mistake.

Tarnar sat on the couch next to her, but not too close, in case she misunderstand his intentions. He responded, “Perhaps Sartre was an alien. He did use that word alienation a great deal. But what I’m trying to tell you, dolce Claudia, is that I am in fact an alien.”

Claudia was delighted that he was starting to open up to her. She had been an open book to him all along. “Ah, sono io, Claudia. You can tell me anything. I also feel like I was dropped into Palermo from another planet.”

“I’m not sure you’re hearing what I’m saying, dear, dear Claudia. I’m not just looking for another reason to stare into the aquamarine currents of your eyes. I want you to take a good look into my eyes.”

Claudia sat up straight and leaned toward the professor. His face went blank as he released the mirror DNA. His irises, usually a dull brown, started spinning, and as they spun they took on the colour of burnished copper. Dark brown was lit with golden yellow from within. Tints of rose and vermillion shot across the space between them, and sprang into Claudia’s eyes, wide as whirlpools.

Claudia continued to look Tarnar directly in the eyes. At last, she said in Italian, “I don’t care if you’re from Alpha Centauri. Come here.”

She pulled him down by the shoulders, and opened her blouse.

💚

Next: The Reign of Error: 🎺 1. Prophecy