The Great Game 🎲 Fallar Discordia

Heaven & Hell

🎲

Purists love spectrums, and love to place themselves in the best light. Yet we all come from somewhere, and that somewhere frustrates our sense of deep roots because it comes from somewhere else, which again comes from somewhere else, till eventually our clawed toes sink into the silt of a muddy continent far away.

We can pride ourselves on being this or that, and we can insist on the spectrum that defines our place in the order of things. Yet the spectrum shifts over time. It contracts in some parts and expands in others. Colours shift like eye-colours across borders, from ebony to chestnut brown, from cerulean to cobalt, from olive green to shamrock.

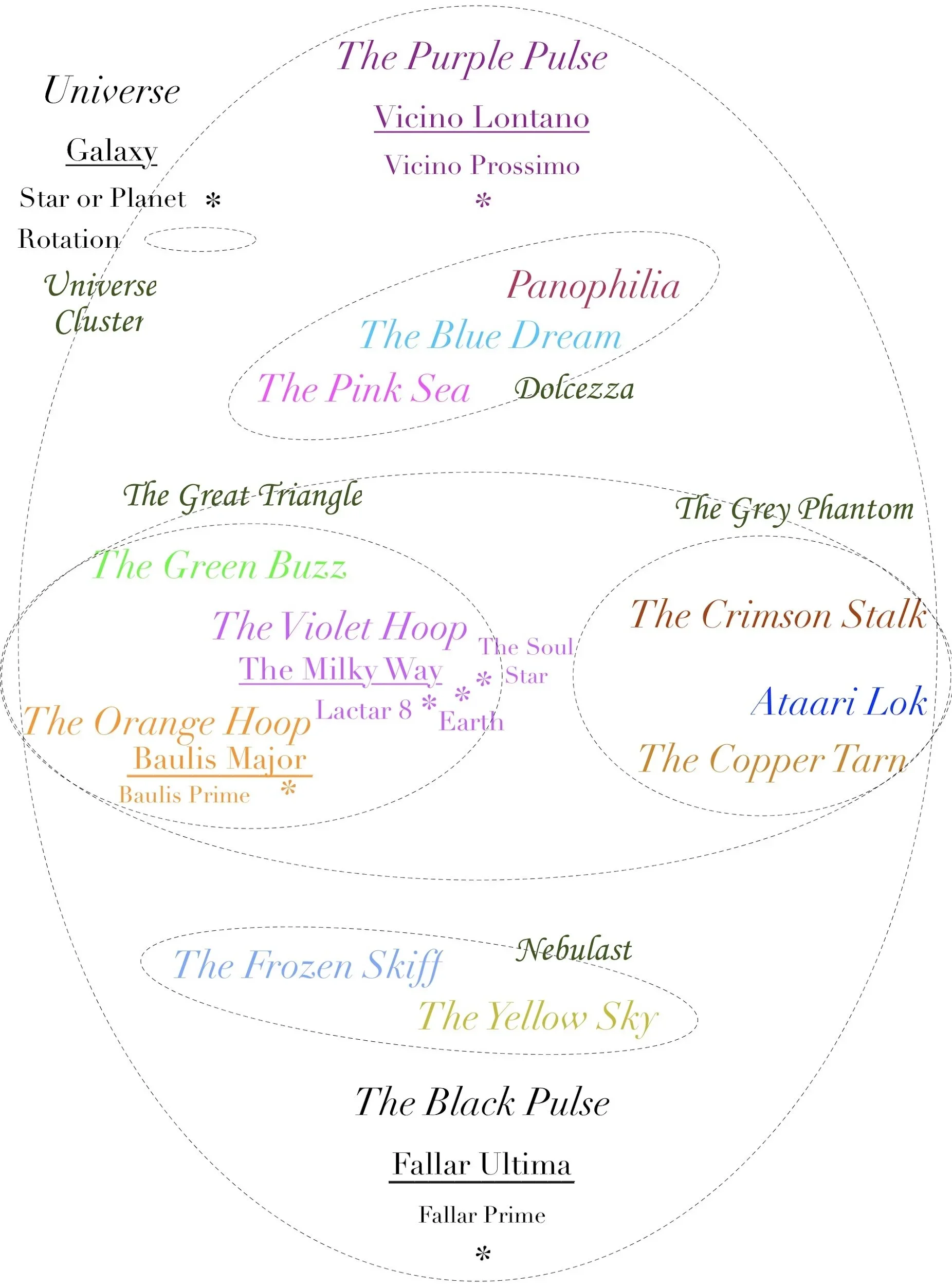

Kraslikan purists insist that the cosmos is smoothly gradated from the nordern Order of the Vicinese to the soodern Anarchy of the Fallarians. In general, they’re right: Dante’s spheres of Heaven, which see more of God’s light (nel ciel che più di sua luce prende), are more likely to be found in the nord; Dante’s circles of Hell, which see more of God’s fire, are more likely to be found in the sood. Yet the devil — and the angel — are in the details.

The error lies in insisting on perfect gradation, in insisting that the nord and sood poles of the cosmos exert their influence on quality to the same degree. This assumes that the matter in which qualities appear is uniformly susceptible to the influence of the poles, as if the further one goes in one direction the stronger this or that quality must be.

Yet this doesn’t work out in practice. For instance, the Blue Dream universe — in the nordern Dolcezza cluster — contains planets of ideal Order and Beauty beyond anything you can find further nord in the Vicinese Federation.

On the Blue Dream planet of Cyan Sogna life is more lawlessly free than on any Fallarian planet, yet it’s also more peacefully ordered than on any Vicinese planet. On Cyan Sogna lawlessness isn’t a prelude to conflict, as it often is elsewhere in the Kraslika. Instead, lawlessness takes the form of a society in which people help each other without being forced to do so by the State. Life is more elegantly beautiful and free than even the finest Vicinese poet could imagine. The Romantic poet Percy Shelley comes closest to imagining it in Adonais, his elegy for Keats. And yet for Shelley it’s the poet, ‘the unacknowledged legislator of the world,’ who burns through the celestial spheres to “the inmost veil of Heaven.” On Cyan Sogna everyone — poets, mechanics, accountants, street-sweepers and even politicians — become “like a star” that “beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.”

Conversely, there are wastelands in the Yellow Sky and the Frozen Skiff that are more unnerving than the Inorridito Gulf, which is located several parsecs sood of Fallar Prime.

While I could supply here a long list of bleak landscapes and treacherous circles in the Yellow Sky and Frozen Skiff, there’s really no point. The main features have already been described in detail by H.P. Lovecraft, who some believe was born in 1890 in Providence, Rhode Island. In fact, he comes from a Frozen Skiff planet called Úzhass. His last name, Lovecraft, is a translation of the common Skiff surname, Navamor.

When he was a travel agent in the metropolis of Zuumskaraa, Navamor filled his promotional brochures with the weird tales told by old geezers and senile grandmothers in the Bezumiya Hills that surrounded the capital city. Due to numerous infractions related to false advertising and billing irregularities, Navamor was fired from his travel-agent job. With the officials of the Bezumiya Tourist Board close on his heels, he flew as far as possible from Úzhass, reaching Earth slightly over a hundred years ago.

Enticed by the frozen stretches of the Far North, he flew his plane over northern Canada, where everything below him seemed identical to his home planet Úzhass. He saw pale skies, empty stretches of tundra, angry stars above, and ugly long scratches beneath. He assumed these scratches were the marks left by giant beasts who had dragged their thrashing prey for hundreds of kilometres.

Landing at Toronto’s Long Branch Airport, Navamor tried his best to fit in to the culture of his new home. But like many immigrants, he couldn’t tolerate the country’s passive-aggressive politeness, the Scottish thriftiness, the Quebecois friendliness, and the stifling democratic values. He realized that the icy, puritanical, elitist society he sought was to the south in America, despite its claims to equal treatment for all. Using the whiteness of his skin as a passport, he became a citizen of the United States.

It was in the city of Providence, Rhode Island, that Navamor usurped the dreary suicidal life of a pulp-fiction drudge named Howard Phillips. From there he went on to write the strange stories of ‘H.P. Lovecraft.’ Well, they were strange to the citizens of New England, but they were well-known bedtime stories in Bezumiya County.

In The Hills of Madness, Navamor did an excellent job of changing the names of places and folklore figures he’d copied into his travel brochures. He also managed to make his New English readers believe that the airplane is a new marvel of technology, and that batteries and stratigraphy are somehow revolutionary. Yet the core of his story was of course nothing new: while he appears to take his reader on a unique journey across an inexplicable alien landscape, in fact his story is taken, word for word, from the tall tales told by drunk yokels in the dusty bars of Bezumiya County. Here, for instance, is what one bumpkin-poet told him in the Brandybore Pub, after grabbing him with his skinny arm and staring into his face like a lunatic:

The Old Ones exercised their keen artistic sense by carving into ornate pylons those headlands of the foothills where the great stream began its decent into eternal darkness.

While Coleridge had to take opium to get strange visions of a sacred river that “ran, / Through cavernous measureless to man, / Down to a sunless sea,” Navamor merely needed to buy a round for the table. In so doing, he got a poetic description that he could write up to intrigue potential tourists:

The adventurous traveller can see many graphic sculptures told of explorations deep underground, and of the final discovery of the Stygian sunless sea that lurked at earth’s bowels. A steeply descending walk (with safety guardrails) brings the visitor to the brink of the dizzy sunless cliffs above the great abyss; down whose sides adequate paths, improved by the Old Ones, led to the rocky shore of the hidden and nighted ocean.

This pilfering of local legends worked like a charm! Tourists — especially tourists who loved horror stories — came from far and wide to the planet of Úzhass, enticed by Navamor’s accounts of the epic battles of ancient history — “the headless, slime-coated fashion in which the Shegseths typically left their slain victims,” and “the curious weapons of molecular disturbance” used by the Old Ones to defeat the Shegseths.

Horror aficionados made up 35% of the travel market in the Yellow Skiff universe, and it was therefore difficult to compete for their attention, what with the prevalence of Gogolwroth horror anthems and 3-D slasher videos. The successful travel agent needed something beyond what could be restaged by the pornographic violence of AI. Navamor’s solution to this was to go further into the backcountry and gather more crazy stories.

In the market town of Ovoshch, Navamor met a milky-eyed seeress who told him that cosmic war would soon be here. The two Great Enemies had sheathed their blinding weapons, yet they would fight again, once the evil had risen from the Eternal Deep. The volva’s eyes glazed over as she spoke in trembling tones of a chasm that “was with ceaseless turmoil seething, as if the earth in fast thick pants were breathing.” She warned Navamor of the time to come, when “the sacred River will sink in tumult to a lifeless ocean. Amid this tumult will be heard from afar ancestral voices prophesying war.”

In the eerily silent town of Dugskullery he found a man with three eyes and a mouth that belched stories of fire. After five or six shots of whiskyice the man told him that “the Old Ones” were once led by Frith Mcollagan, Myth Macrominy, and the most ancient of all, the Great Rinagin Raganin. These Old Time warriors appeared — “only appeared!” he shouted to the invisible wraith hovering above over their table — to have triumphed over the sluggish Shegseths, the giant worm-like monsters hidden deep inside the Mountains of Madness.

Navamor was recording everything the madman said, and was already planning how the lunatic’s words might be used to form a larger, grander narrative. Yet that project would have to wait. For the moment he needed to craft a brochure of varied horrific seduction, one that would touch the sentimental horror fan as well as the hard-core lover of godless gore.

The more the madman talked, the more Navamor saw how he might give a great spine-wrenching shiver to the tourists if they believed that the hideous Shegseths, who appeared to be defeated, were in fact still lurking in the bowels of Úzhass:

In the occult county of Bezumiya there remains a sombre and recurrent type of scene in which the Old Ones were shewn in the act of recoiling affrightedly from some object — never allowed to appear in the design — found in the great river and indicated as having been washed down through waving, vine-draped cycad-forests from those horrible westward mountains.

In his brochures, Navamor stressed that this cosmic horror must be felt, not just seen on paper or screen. It must be scented in person, sniffed out during a safe and comfortable tour, one that was surprisingly inexpensive given the richness of horrors on offer. He stressed that it was only by descending into the ancient caves in person, and by standing stock-still in your own quivering skin that you could hear for yourself the eery voices of the Ancient Deep.

Then — and this was guaranteed by Zuumskaraa Wonder Tours — the feeling of Infinite Horror would creep up from the pit of your stomach into your trembling brain. You would see, coming at you from the very walls, the spectre of some horrible Magalithic Power rising from the deep. Then, slowly, the Grand Shegseth, the monster with a warrior ethos that burrowed up from the abyss, would flood the subterranean tunnels of your id.

Navamor promised that every tourist who bought a deluxe all-inclusive ticket to The Hills of Bezumiya Tour would come back screaming in bliss from the horrific reverberating primal OM of the caves. He would run “along ice-sunken megalithic corridors to the great open circle, and up that archaic spiral ramp in a frenzied automatic plunge for the sane outer air and light of day.” The excited tourist would go running like mad past squawking, confused penguins and souvenir vendors back onto his own tracks, into the waiting luxury bus to the airport and back to the safety of his own city.

Once safely back in his honeycomb apartment, the tourist would take another look at the brochure that brought him to the brink of the abyss, and at the promise kept that brought him back, in comfort, to his blessed life and benign fate. Whether or not the surviving tourist would credit his lucky escape to chance or benign fate, was the subject of follow-up seminars offered by Navamor and the Zuumskaraa Wonder Tours team.

The coup de grace would come even later, when the true connoisseur of horror would savour the delicious horror of knowing that he would never be able to forget the unholy things he had seen. This was the solution that kept the seductive problem intact: he should have never, never set foot in that dreadful place, and yet he would not be able to stop himself from going again.

Navamor guaranteed that, after his adventures in the Hills of Bezumiya, the tourist would say the following to himself each night before he said his prayers:

Would to heaven I had never approached the monsters, but had run back at top speed out of that blasphemous tunnel with the greasily smooth floors and the degenerate murals aping and mocking the things they had superseded — run back, before I had seen what I did see, and before my mind was burned with something which will never let me breathe easily again!

And yet the tourist would come again next year, descending again into the shining tunnel, listening once more for the approaching echoes of the shapeless, carnivorous Deep.

🎲

Navamor’s brochures promised that the tourist’s journey would be totally epic and artistically complete. It would start in terror, climax in a stark encounter with the soulless monsters of the deep, and end with the rosy hue of reconciliation with his loved ones, with his local priest, and with his family in his native city, where he could rest once again within its strong walls.

Later he would on occasion remember with a delicious shudder the giant City of the Dead choking in the icy peaks of Bezemiya, on the ghastly planet of Úzhass. He would convince himself that his planet wasn’t like that. He would tell himself the fairy tale that his city’s walls were strong as those of ancient Uruk, and yet far older. He lived in the Eternal City.

And in his Eternal City he would listen to the Sacred River, flowing into a Garden where he was sitting, drowsy with the thought of oncoming Sleep, drowsiness numbing his senses like the finest opium, listening to the murmuring secrets of the River.

Over the murmur he would hear the sweet notes of a dulcimer, played by Carlotta Antonelli as she walked down Via Veneto, with her dark eyes ablaze and her burning ears listening through the bleating cars to the heavenly thunder of the Nightingale.

🎲

Next: 🎲 Spies

Contents - Characters - Glossary: A-F∙G-Z - Maps - Storylines