The Double Refuge 🇮🇳 The Fiction of Doubt

The Two Adams

Attar & the Loss of Eden - Plot Box 1: An Anxious Saleem - Plot Box 2: Attar's Journey - Mystical Gems

🇮🇳

Attar & the Loss of Eden

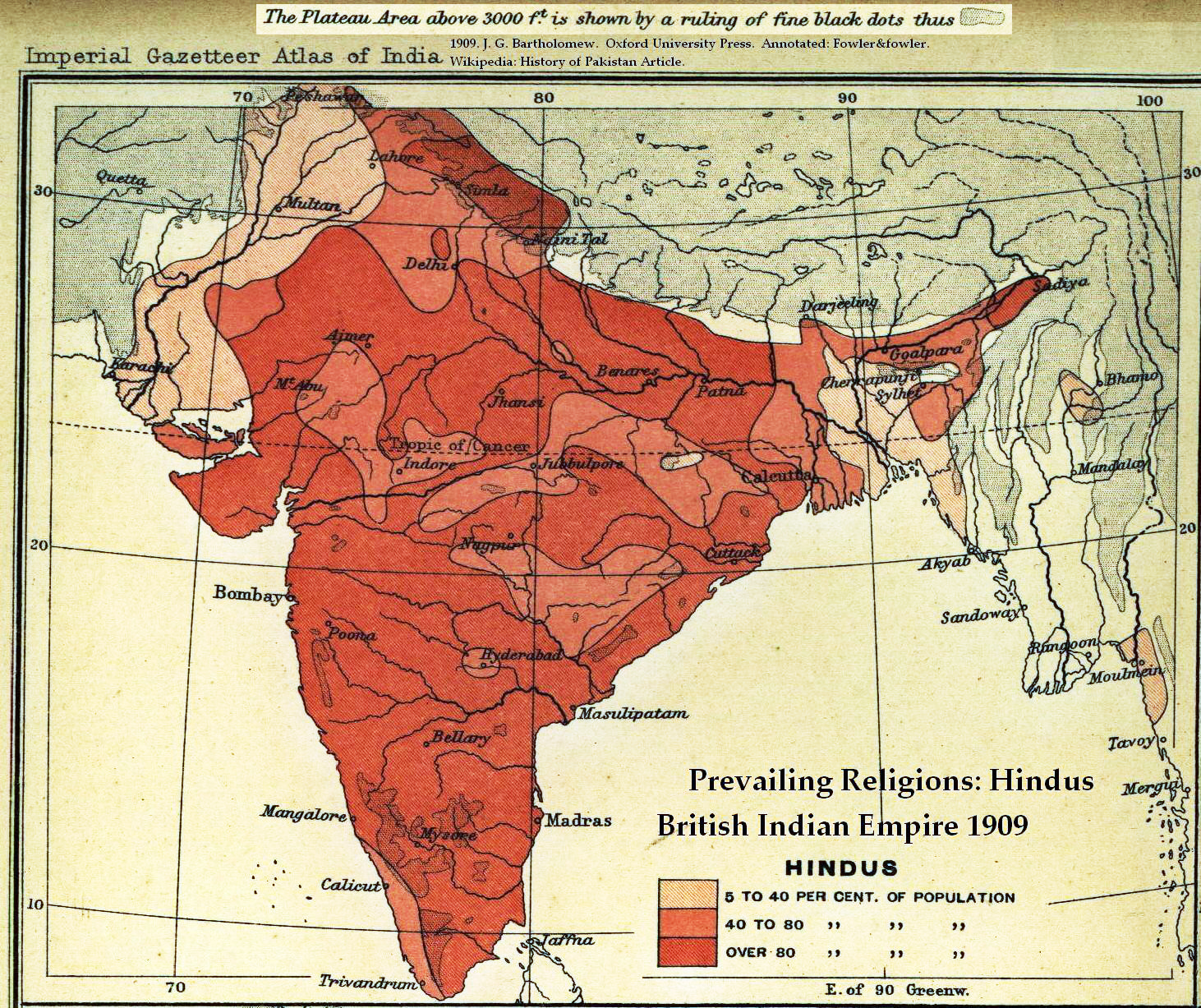

Rushdie begins Saleem’s personalized account of subcontinental history in Kashmir. This is appropriate, since Kashmir has strong (and deeply contentious) links to both India and Pakistan, the two political powerhouses in the novel. Kashmir's future remains uncertain politically and historically (even to this day), which echoes what Rushdie suggests about India, and perhaps even more so about Pakistan.

Plot Box 1: An Anxious Saleem Writes about his Grandfather's Return to Kashmir

Rushdie's narrator, Saleem, is writing his life story in a pickle factory in Bombay in the novel's present, which is immediately following the 1975-77 Emergency, in which Indira Gandhi suspends the Indian parliament. This anti-democratic act, along with Saleem's skepticism about the open, democratic nature of subcontinental society, has him worried. (In addition, India has just got the nuclear bomb and tensions are still high between India and Pakistan.) He's therefore anxious to write his account before India and his body (which is prematurely old) fall apart. ❧ Going back in time, Saleem recounts the story of his grandfather Aadam Aziz, who returns to Kashmir in 1915, after having become a doctor in Europe. Saleem's account then follows the life of Aadam, who rejects tradition in Kashmir, and moves to Amritsar (Chapter 3) and Agra (Chapters 4-5). Aadam then stays behind in Agra while the narrative shifts to his daughter Amina, who moves with her new husband Ahmed to Delhi (Chapter 5-6) and then finally to the city of Saleem's birth, Bombay (Chapters 7-19). (Bombay is of course now called Mumbai, but in the novel Saleem is eager to get back to Bom! and he writes about the bomb in Bombay, so the old name is important). ❧ The first section of the book (Chapters 1-8) give readers a fictional, personalized take on some of the key moments of early- and mid-20th century history, especially the Amritsar Massacre in 1919, the communal politics in the 1930s and 40s that lead to the Partition of the Indian subcontinent, and the departure of the British in 1947.

A key narrative linkage occurs when Aadam's involvement in Agra with "the Free Islam Conference" (which opposes the creation of a separate Muslim state, the eventual Pakistan) anticipates Saleem's involvement with the Midnight's Children's Conference, which aims to unite the diverse religious, linguistic, and ethnic populations of India.

Rushdie also turns Kashmir into a symbolic Garden of Eden. This is important, for Midnight's Children isn't a work of history that has clear references to dates and events. Rather, it's a work of mythologized and idiosyncratic fiction that also has a strong historical bent. As a writer, Rushdie takes advantage of the powerful tools of myth, metaphor, allegory, and allusion. [Please note that I use the word myth in a very neutral manner, as a way of signalling elements that people associate with both myth and religion. Like Donniger O'Flaherty in Other People's Myths (1988), I'm suspicious of any categorical separation of myth from religion.] To Aadam Aziz, Kashmir represents the magic of mythical history: it's here that he sees the “world was anew again,” and it's here that after a “winter’s gestation in its eggshell of ice, the valley had beaked its way out into the open.” Saleem also refers to the Koranic version of cosmogony, in which God “created Man from clots of blood.”

This religious language signals a profound conflict in his grandfather. For Aadam is a Modern man, a contemporary version of the old Jewish figure, who has been away from the old mythic realm for a long time. He left Kashmir to study Modern medicine, a field which, like geology and astronomy, has deep European Renaissance and Enlightenment roots. Because his foreign studies are so deeply implicated in the Modern split of science from religion, Aadam no longer sees Kashmir the way his grandfather did. He no longer sees the world in terms of the old traditions, let alone see it in terms of the mysticism of Attar. Literally and symbolically, he finds it difficult to “recall his childhood springs in Paradise” (MC 10-11).

Aadam’s father, old Aziz sahib, is a version of Aadam as he might have been had he stayed in India and had he not eaten so heartily from the forbidden fruit of knowledge that he found hanging ripe from the branches of Heidelberg.

An old gem-dealer, old Aziz sahib exists in a prior mythic state, in a mystical and pre-historic unity with the serenity and otherworldliness of Eden. Rushdie the iconoclast can’t help himself from at least partly debasing with humour this ideal geographic set-up: it isn’t an overdose of spiritual energy, but rather a stroke, that drops a veil over old Aziz sahib's brain. This stroke turns out to be a stroke of good fortune, for it animates the old man’s inner world with a recognizable variant of Attar’s 30 birds:

in a wooden chair, in a darkened room, he sat and made bird-noises. 30 species of birds visited him and sat on the sill outside his shuttered window conversing about this and that. He seemed happy enough. (MC 12)

Rushdie further evokes a humorous combination of senility and Sufi annihilation when the old man sits “lost in bird tweets,” is “deprived of his birds,” and dies “in his sleep” (MC 14, 28).

Plot Box 2: Attar's Journey & Midnight's Children

Attar's 12th century Conference of the Birds is a long mystical poem in which birds debate the value of their journey and then travel over the valleys of mysticism to the Mountain of Qaf. At the start of their journey they are told that the King of Birds, the Simurg, resides on the peak of Mount Qaf.

Eight-Pointed Star Tile with Simurgh, late 13th century. Ceramic, Brooklyn Museum (Wikimedia Commons)

When they get there, the 30 remaining birds — si murgh in Persian — realize that there's no immanent King; rather, their united spirits are the transcendent King (who lies beyond any type of icon or number). This realization makes them transcend their limited selves and they reach mystical annihilation. ❧ Attar's poem openly structures Grimus and covertly yet powerfully structures Midnight's Children. As comic and quietist as old Aziz sahib’s vision may seem, it's also germinal. It takes dynamic political and narrative form: first in Aadam's Free Islam Convocation (which tries to unify Hindus and Muslims in one state); second, in the Midnight's Children's Conference (which Saleem tries to convene in order to unite the diverse personalities of India); third, in the songs of Saleem’s sister Jamila (which the Pakistani generals use in a militaristic manner); and fourth, in the structure of the novel itself: Saleem writes thirty chapters and speculates on the meaning of the 31st chapter, the nature of the annihilation to come. Playing a sort of numerological game (beloved by mathematicians and mystics alike), Rushdie conflates the happy ending of Scheherazade, at 1001 nights, and the ambiguous ending implied in his use of Attar's 31.

While Old Aziz sahib's blissful oblivion is suspect in some ways, it leads to serious themes and motifs. The old gem dealer may be guilty of what Rushdie in an essay on Orwell calls living inside the whale -- when the real world outside should occupy one’s attention (Imaginary Homelends 93-95). Aadam Aziz is willing to face the Modern world, yet his father is too old and too deep in mystic oblivion. Old Aziz sahib's Sufi vision may be passé from a Modernist theological angle, yet it gets transmuted into a positive symbol of Muslim cultural heritage, one which embraces change as well as other cultures and religions, at least in the case of Aadam's Free Islam Convocation and Saleem's Midnight's Children's Conference. Sadly, this Islamic symbol of the Simurg on top of Qaf Mountain also takes a more militant form in the case of Jamila's bird-like singing, which is used to push Pakistani soldiers into battle. This double, opposing use of Attar's symbolism isn't new in Rushdie's fiction: we've already seen it in the character Grimus, who in the name of mysticism takes authoritarian control of Calf Mountain. Like the Pakistani generals, Grimus takes the beauty of the Simurg and turns it into a grimace.

Rushdie makes the militaristic use of Attar all the more tragic by explicitly linking old Aziz sahib and Jamila. Saleem tells us that his great-grandfather’s “gift of conversing with birds” descended “through meandering bloodlines into the veins” of Jamila (MC 107). He tells us that his sister “talked to birds (just as, long ago in a mountain valley, her great-grandfather used to do)” (MC 293). Saleem emphasizes the poetic and mystical associations of the ghazals she sings, and underscores the mix of divine and human love which characterizes this Persian and Urdu poetic form:

I listened to her faultless voice … filled with the purity of wings and the pain of exile and the flying of eagles and the lovelessness of life and the melody of bulbuls and the glorious omnipresence of God. (MC 293-294)

Rushdie's choice of Heidelberg as the location of Aadam's education may make sense here for at least two reasons. First, it's a venerable Western institution devoted to humanistic knowledge: founded in 1386, it shifted to humanistic education in the 15th century. This type of knowledge was crucial in the questioning, and for many, in the rejection of religion.

One Kashmiri morning in the early spring of 1915, my grandfather Aadam Aziz hit his nose against a frost-hardened tussock of earth while attempting to pray. (Chapter 1)

Less obviously, Heidelberg is also associated with Muhammad Iqbal, the famous Pakistani poet who promoted Modernism, poetry, Sufism, and also the separate Muslim state of Pakistan. While Sufism, and Attar's Sufism in particular, is usually symbolic of unity in Rushdie's fiction, it's also at times linked to subcontinental division.

One might also see old Aziz sahib’s mysticism in light of Omar Khayyam’s Ruba’iyat, a work that comes from the same century and the same town (Nishapur, in present north-eastern Iran) as Attar’s Conference:

You and I only talk this side of the veil;

When the veil falls, neither you nor I will be here.

Once the veil of mysticism has fallen over the brain of old Aziz sahib, he's out of the story. He's somewhere we can’t see; he's no longer here. Like Khayyam, Rushdie may be skeptical of mysticism, yet he nevertheless makes sure to include its symbolism in his writings. One might even liken Rushdie's skepticism to Khayyam’s in that the Persian poet was famous as an astrologer yet didn’t seem to believe in it.

🇮🇳

Mystical Gems

Old Aziz sahib’s conference is transmitted from generation to generation, beginning with the feisty Aadam Aziz. Aadam’s surname links him to Forster’s Indian protagonist in A Passage to India, who at the end of the novel has retired to a remote princely state. It's important to note that in the Ivory-Merchant film he reaches his beloved Kashmir.

Forster’s Aziz is also a doctor whose Western education alienates him from his Muslim roots. Rushdie's Aziz is much more alienated than Forster’s, however, which makes sense in that the latter is personally betrayed by the English. While Aadam Aziz is strongly affected by the brutality at Amritsar, he’s also frustrated by the stubborn piety of his wife and enraged at the ongoing religious indoctrination and communalism that’s tearing his country apart. In many ways he longs, like Mirza in the Verses and Rai in Ground, for the secularism of the West.

While Rushdie’s Aadam has no Eve as such, he is seduced into marriage by visions of Naseem behind the perforated sheet (the name of Chapter 1), he does have his run-in with God, and he is chased by the Old Testament anger of Tai from the paradise of Kashmir.

Adam's fall, seen in terms of a “failure to believe or disbelieve in God” (MC 275), also derives from the traditional source: the forbidden pursuit of knowledge. Rushdie situates this source not only in the godless West (so joked about in many of his novels), but also in German lands, cradles of the great architects of uncertainty and revolt — Marx, Freud, Nietzsche, Einstein, etc. While Aadam’s German friends mock “his prayer with their anti-ideologies,” Aadam doesn’t capitulate to their Orientalism, in which India “had been discovered by the Europeans.” Saleem comments that “what finally separated Aadam Aziz from his friends” was their belief “that he was somehow the invention of their ancestors” (MC 11).

Aadam’s fall is expressed in general religious terms as well as in specific Islamic terms: his decision not to perform his morning prayers echoes what Milton calls “Man’s First Disobedience”; his refusal to “kiss earth for any god or man” (MC 10) echoes Iblis’ refusal to bow before Aadam, God’s first human creation. At one point, Iblis (the Muslim version of Satan) is in the highest heaven and closer to God than any other angel. He resents God’s interest in man, however. Feeling that his birth from fire makes him superior to this new creature made of clay, he refuses to bow before anyone but God.

While Rushdie has a great deal of sympathy for Aadam, his secular hero, he also suggests that in refusing to bow, in revolting against God and Islam, Aadam loses something very precious: the result of his decision never to “kiss earth for any god or man” is that rubies and diamonds drop miraculously from his nose and eyes (MC 10). It's crucial (yet easy to forget) that Aadam is the son of old Aziz sahib, the gem dealer.

What bedazzled old Aziz sahib's mind into mystical oblivion is impossible for Aadam Aziz to recover.

Old Aziz sahib's mystical gems literally and symbolically bang him in the nose, making it bleed. Blood then becomes a leitmotif that can be taken to symbolize the difficult history of his heirs in the fallen world. Key instances of the leitmotif include the bloodied perforated sheet of Aadam Aziz's wedding night and the blood type which uncovers Saleem's illegitimate birth.

Aadam Aziz's rejection of religion has the same consequence as that suffered by Iblis: a protracted, losing battle against God. We see this later in his ranting old age, yet we also see this early on as well, in his battle against religious extremists in Agra. The Free Islam Convocation which he supports against the Muslim League isn’t an entirely fictional concoction, as Parameswaran explains:

While the Muslim League was firmly established and intent upon the creation of Pakistan, Sheikh Abdullah, a Kashmir Muslim, founded the Muslim National Conference, which leaned towards Gandhi’s undivided India and against the Muslim League. Sheikh Abdullah lived long after Independence, but Rushdie’s Mian Abdullah [Rushdie's Hummingbird], founder of Free Islam Convocation, is killed by six assassins, ‘six crescent knives held by men dressed all in black,’ but before he dies there is a supernatural aura given to him. (The Perforated Sheet 23)

In Shame the death of the anti-communalist crusader Mahmoud is also accompanied by the supernatural — in that case, “a sound like the beating wings of an angel” (S 62). The Hummingbird’s fate is thus shared by Shame's cinema owner who attempts the impossible task of uniting Hindus and Muslims in a double bill. Like Rushdie’s other tolerant mystical figures - from Lifafa Das to Sufyan - the Hummingbird and Mahmoud are persecuted by those who want division rather than unity, by those who want strict definitions of culture rather than eclectic hybridity.

The name of Sheik Abdullah’s group was originally Conference, as in Attar, whereas Rushdie modifies it to Convocation, returning to Conference only with Saleem’s Midnight’s Children’s Conference. This may put some readers off the Attar trail, yet given the mention of old Aziz sahib’s 30 species of birds, and given Saleem’s yearning for unity and his fear of annihilation, it’s not hard to see through this shift in names.

🇮🇳

Next: The Rock: Amina Sinai