Crisis 22

Mirrors

Overview - The Mirror Up to Nature - Poetry & Unified Sensibility - Tragedy & Comedy - Achilles & Arjuna

🪞

Overview

This page illustrates how literature deals with difficult issues like tragedy, catharsis, morality, and war, and how it can help us retain a critical distance and a sense of humour. More specifically, it illustrates how drama, poetry, and prose mirror our lives and our problems in Shakespeare's play Hamlet, Auden’s poem “The Shield of Achilles,” Rushdie’s novel Shame, and Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five.

My goal here isn't to advance a literary theory, but to note how the qualities of literature help us get at the present crisis: Putin acts like the regicidal Claudius in Hamlet, except that he never repents; Putin's decision to go to war and his repetition of bitter, self-serving reasons is reflected in Auden's dystopia where "nothing was discussed," where hundreds of thousands line up to kill each other, and where the mad logic of war leads entire nations not to glory but to disaster: “Out of the air a voice without a face / Proved by statistics that some cause was just / … Column by column in a cloud of dust / They marched away enduring a belief / Whose logic brought them, somewhere else, to grief."

The present situation is so grim that it would require a Rushdie or a Vonnegut to find a compassionate or humorous angle among the doubling down on lies, the multiplication of manipulation, and the unforgiving brutality of violence. For Rushdie does just this amidst the communal horror of Partition (the violent division of the subcontinent in 1947). And Vonnegut presents us with a vision of simple redemptive decency immediately following the bombing of Dresden.

The situations that Rushdie and Vonnegut deal with are close to us historically, yet Shakespeare's Renaissance Hamlet and Auden's Classical Achilles remind us that the mirroring quality of literature isn't something new. It goes way back — to the first great works of Western and Indian literature, the Iliad & Odyssey, the Mahabharata & Ramayana. These poetic epics focus on specific wars, yet they also supply wide-ranging insights into psychology, culture, philosophy, religion, etc.

🪞

The Mirror Up to Nature

Hamlet tells his actors to act realistically, so that the king will be moved to show his guilt. He then comments on the value of literature: it shows us our very nature, as well as the nature of the world we live in:

[…] suit the action to the word, the word to the action […] for any thing so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as it were, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her [its] own feature, scorn her [its] own image, and the very age and body of the time his [its] form and pressure.

Expanding on Hamlet’s suggestion, we might see literature as a diverse and free-floating set of well-placed mirrors that continually reflect what people are thinking and feeling.

In this analogy, a play is like a large mirror that allows us to see the interaction of humans in real space (although of course the stage is a special sort of real space, configured by specific words and actions along a specific plot line). A poem on the other hand is like a smaller mirror: it reflects an image, metaphor, symbol, or idea which everyone can see even though it may have seven (or seven hundred) interpretations, depending on our point of view in time and space.

The more the metaphor is extended, the more it becomes specific, that is, the more it mirrors an extensive yet precise scenario which starts to look like real life.

A novel is like a very long sequence of mirrors, reflecting a more detailed sequence of thoughts and feelings. This long sequence gets us closer to the complex structures of such things as psychological landscapes, cultural narratives, political ideologies, and philosophical theories that deal with who were are (ontology) and what we can know (epistemology). The number of novel mirrors required to do this is astronomical, and the more mirrors the author uses the more the readers get a precise geolocation of the historical moment.

In this project I’ll be looking at novels which peek into important historical moments in Russia: Nikolai Gogol holds up a quaint mirror to rural 19th century Russian society in Dead Souls (1842); Fyodor Dostoevsky holds up a grimy mirror to 19th century Saint Petersburg in Crime and Punishment (1866); and Mikhail Bulgakov holds up an unnerving sorcerer’s mirror to Soviet Russia in The Master and Margarita (1967). The other novels I look at put an even greater emphasis on the historical moment and on the flow of history from one decade to the next: Graham Greene mirrors the mid-1950s transition from French to American violence in Vietnam in The Quiet American (1955); Christopher Koch holds up a puppet theatre screen of shifting images that intimate the transfer of power from Sukarno to Suharto in 1965 Indonesia in The Year of Living Dangerously (1978); Salman Rushdie holds up a magical and at times terrifying mirror to 20th century subcontinental history in Midnight’s Children (1981) and Shame (1983).

Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) is perhaps the most curious novel I’ll look at in Crisis 22. Vonnegut sets up two complex sets of mirrors that face each other, one in Germany and Dresden in 1945, the other in and around New York State in the 1960s. These mirrors allow the reader to see World War II Germany in light of Vietnam War America, and vice-versa. In addition, he places a tiny mirror deep in space, allowing the reader to see the events of this world from the imaginary planet of Tralfamadore, which is itself a reflection of the cracked mind of the protagonist Billy Pilgrim.

🪞

Poetry & Unified Sensibility

Poetry has many forms, the oldest of which, epic poetry, resembles the novel. Here, the panorama is vast, and the meanings are deep and wide. Today, however, this wider expression of poetry has largely been usurped by novels, book-length studies, and TV shows like Deadwood, The Sopranos, The Americans, Homeland, Breaking Bad, Fleabag, The West Wing, House of Cards, The Crown, White Lotus, etc. Most of what we think of poetry today is of the shorter variety.

This shorter poetry has at least two virtues that are relevant to complex themes such as war and history. First, shorter forms of poetry can condense wide, open-ended topics so that they can be seen in or through an image, symbol, or turn of phrase. For instance, when Hamlet says, the time is out of joint, this refers to his world (where through cursed spite he was born to set it right), but it can also be a condensed way of saying that the machinery of this world is malfunctioning, or that Time itself is out of its natural anchor or pivot, from within which it could smoothly move or rotate.

Because we use words, images, ideas, and narratives in understanding reality, literature responds to our basic psychological makeup. Key to this makeup are two component parts: thinking and feeling. Often, these get separated, and drastic consequences ensue — as, for instance, when we see a line of rational argument about Ukraine’s national sovereignty and forget about the deep emotions that many Russians feel about Greater Russia, which conveniently includes what they call Little Russia, or Ukraine. Their rational argument vanishes into thin air simply by looking at international law or at the agreement they signed in order to take their nukes out of Ukraine. But in the place of this evaporated argument comes an etherial mist, which turns into a watery shroud, from which they proclaim, with all the righteousness of the Orthodox priest, that Ukraine is Russian.

Literature, especially poetry, is helpful here, since poets in particular are skillful at combining thought with feeling, so that we enter into their work — or into any situation — with these two fundamental aspects of human psychology engaged. A hundred years ago T.S. Eliot called this connection of thought to feeling unified sensibility. One might also call it being in touch with our feelings, being a whole person, Romanticism, yoga, etc.

Literature doesn’t just urge us to see and feel the moment; we’re also urged to ponder its meaning as well, and to compare it with other situations that press upon us in the real world. Literature directly pushes us to do this through setting, character, configuration of scene, etc., and it subtly pushes us to do this though image, symbol, paradigm, ambiguity, etc. According to Eliot’s theory, all these elements combine to connect our thoughts and feelings, and to connect our inside world with outside reality. Because this outside reality is always changing, and yet at the same time always entering into us, we too are always changing:

The knowledge imposes a pattern, and falsifies,

For the pattern is new in every moment

And every moment is a new and shocking

Valuation of all we have been. (T.S. Eliot, East Coker II)

🪞

Auden’s poem, “The Shield of Achilles,”supplies a powerful instance of the way literature can 1) mirror a personal sense of history and politics, 2) blend emotion and thought, and 3) urge us to ponder the meaning of it all. In the poem, Thetis (the mother of the great warrior Achilles) looks at the shield Hephaestus (the blacksmith god) is making for her son. Auden contrasts the beautiful things Thetis sees on the shield with the images of war and suffering that Hephaestus also depicts. Hephaestus includes a haunting mini-scenario, which is at once universal and self-contained, ordinary and extraordinary, vague and concrete, brutal and understated:

Barbed wire enclosed an arbitrary spot

Where bored officials lounged (one cracked a joke)

And sentries sweated for the day was hot:

A crowd of ordinary decent folk

Watched from without and neither moved nor spoke

As three pale figures were led forth and bound

To three posts driven upright in the ground.

The mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes liked to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

Auden skillfully sets the tragic personal within the grand historical, playing the grubby horror of a public torture scene against the mass and majesty of the world.

🪞

Tragedy & Comedy

Two revitalizing qualities of literature are catharis and humour. In catharsis a writer reworks a difficult experience so that we can grasp it and at some point (or in some way) also leave it behind us. In catharsis we go through the depth of an experience. We go into all its subtle anguish and uncertainty, to arrive at the other end with a greater understanding of it. This understanding isn’t based on a philosophy which distances us from it, but on knowing the details of the problem, on facing these details and on feeling them — that is, on feeling them as much as vicarious experience can be said to emulate feeling.

Humour on the other hand allows us to distance ourselves emotionally from the predicament, seeing it as quaint, absurd, or incongruous. We can therefore see the predicament as something we don’t necessarily need to get caught up in, or be overwhelmed by. Writers such as Bulgakov, Vonnegut, and Rushdie are particularly skillful at finding humour in the grimmest of situations, allowing us an inner release which the reality of war and tragedy seldom allow in real life.

For instance, in Shame (1983), Salman Rushdie depicts a well-intentioned, idealistic cinema owner named Mahmoud, who dares to show a Hindu-Muslim double bill in pre-Partition India. The “double-bill of his destruction” is at once humorous and tragic, allowing us to bear to look at a paradoxical and terrifying situation in which people kill other people because they have different ideas about a benevolent and merciful God.

Highlighting the ludicrous degree to which religion divides the citizens of pre-Partition Delhi, Shame’s narrator remarks that “going to the pictures had become a political act. The one-godly went to these cinemas and the washers of stone gods to those; movie-fans had been partitioned already.” Mahmoud revolts against this division, asserting that it’s time “to rise above all this partition nonsense.” So he plays a film in which cows are set free along with another film in which cows are eaten (what Rushdie comically calls the “non-vegetarian Westerns”). Mahmoud thus indulges his “mad logic of romanticism” and dares to exhibit a “fatal personality flaw, namely tolerance.”

Another instance of using comedy to plunge deep into tragedy occurs in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). For such a short novel, it does an amazing job of bringing its reader into the trenches of World War II and into the bombing of Dresden (which the author himself experienced). Vonnegut constantly juxtaposes the comic mundane and the tragic extraordinary, urging his reader to see as insanity what we we accept as normality. For instance, in his description of a sci-fi novel “about a robot who had bad breath” and “who became popular after his halitosis was cured,” he suggests that the horrors of napalm bombing are happening not just out there in a science-fictional cosmos and not just over there in some fantastical futuristic dimension, but right here in 1969, the year the novel was published:

But what made the [sci-fi] story remarkable, since it was written in 1932, was that it predicted the widespread use of burning jellied gasoline on human beings. It was dropped on them from airplanes. Robots did the dropping. They had no conscience, and no circuits which would allow them to imagine what was happening to the people on the ground.

Trout's leading robot looked like a human being, and could talk and dance and so on, and go out with girls. And nobody held it against him that he dropped jellied gasoline on people. But they found his halitosis unforgivable. But then he cleared that up, and he was welcomed to the human race.

The above scenario is also a good example of how literature supplies us with paradigms of perfection and patterns of imperfection. These help us to develop critical and contextual understandings, and to sort out exactly what it is we’re fighting for and against. By likening American use of napalm in Vietnam to a crazy sci-fi scenario, Vonnegut’s American readers see a model of imperfection more easily, much more easily than if they were given a lecture on the ethics of their foreign policy. Satire is often seen as showing society a mirror, within which people see everyone’s faults except their own.

The opposite paradigm can be seen toward the end of Slaughterhouse-Five, after the Americans, Canadians, and Brits have bombed Dresden to rubble. The survivors ascend from the bomb shelters into the landscape above, which resembles the surface of the moon. Where are they to eat or sleep? Vonnegut is an infamously secular and iconoclastic author, yet he answers these questions with reference to one of the most fundamental narratives in Christianity. He displaces a specific element of the Nativity — the decency of the innkeeper — two thousand years into the future, into a time and place where, like in Ukraine today, Christians are bombing their brothers to smithereens:

There was a blind innkeeper and his sighted wife, who was the cook, and their two young daughters, who worked as waitresses and maids. This family knew that Dresden was gone. Those with eyes had seen it burn and burn, understood that they were on the edge of a desert now. Still — they had opened for business, had polished the glasses and wound the clocks and stirred the fires, and waited and waited to see who would come. […]

The blind innkeeper said that the Americans could sleep in his stable that night, and he gave them soup and ersatz coffee and a little beer. Then he came out to the stable to listen to them bedding down in the straw.

"Good night, Americans," he said in German. "Sleep well."

🪞

Achilles & Arjuna

The unifying elements of ✅ identifying with characters and ✅ seeing situations within larger frameworks of culture and history are as old as literature itself. We see them in the world’s oldest epic, Gilgamesh, and in the foundational epics of early Greece and India. In the Iliad we’re placed in an early Greek world of warring city-states, where the virtue of honour is paramount. Yet after a decade of war, we’re urged to feel the sorrow Priam feels when he visits his enemy Achilles, who in his outrage has just killed Priam’s son and has dragged the body across the battle field. Honour, it turns out, isn’t as important as compassion and love. In the Mahabharata we’re placed in a north Indian war around the start of the Mauryan Empire (322–184 BC), a time when the ideal of dharma or duty was prominent. At a key moment in the epic, we’re urged to feel the anguish Arjuna feels at having to go to war against his cousins and uncles. Although it tears him apart, Arjuna learns from Krishna that his dharma, his duty to what’s just and right, trumps his loyalty to family.

These two foundational epics are rife with outrage, anguish, and sorrow, feelings which many Russians and Ukrainians are no doubt feeling in the course of the present war between erstwhile Slavic brothers. I try to get at something of this internecine tragedy in my poem “The Tao of Putin,” where I contrast the mystical butcher depicted by the Daoist writer Zhuangzi to the imperialistic butchery of Putin (I provide preface and notes for this poem in 🦋 The Tao of Putin). The former has an intuitive insight into the anatomy of nature, while the latter cuts “with the sharpest of blades, extracting the vile Nazi within.” While the Daoist sage sees the world around him as an uncarved block of simplicity and peace, Putin sees it in hierarchical nationalistic terms:

As a result of his vision of the world, Putin wages war on his closest neighbour, on the people he believes are fundamentally like him: Russian.

Auden’s poem gets powerfully at the futility and the tragedy of war, whether it’s the millions of troops lined up by Hitler or the hundreds of thousands lined up by Putin:

Out of the air a voice without a face

Proved by statistics that some cause was just

In tones as dry and level as the place:

No one was cheered and nothing was discussed;

Column by column in a cloud of dust

They marched away enduring a belief

Whose logic brought them, somewhere else, to grief.

Poetry manages in a phrase or stanza to sum up things in a succinct way, using density of symbol and ambiguity of meaning. For instance, “nothing was discussed” sounds simple enough, and very vague, yet it can be applied to the fundamental differences between democratic Ukraine and authoritarian Russia, and to the basic reasons we’re willing to back Ukraine: democracy, free expression, and the international right to territorial sovereignty.

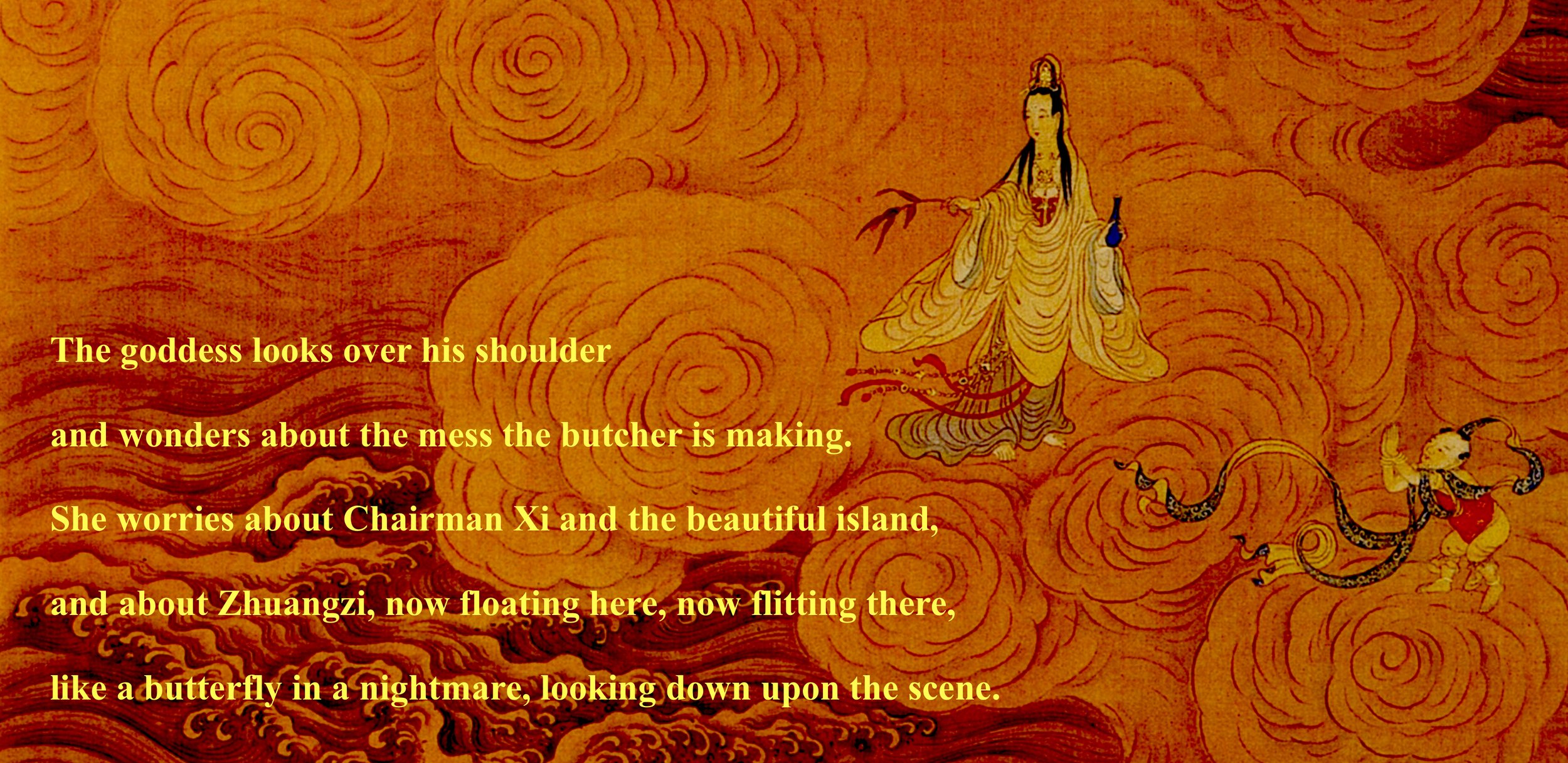

I also use Thetis’ gaze at the end of my poem “The Tao of Putin” (which, again, I explain more fully in 🦋 The Tao of Putin). In my poem the Greek goddess morphs into the Chinese goddess of mercy, Guanyin. She looks over the shoulder of Putin as he butchers his fellow Slavs. She worries about Taiwan and about what Xi might do to it. The ghost of the philosopher Zhuangzi — who is famous for his extended conceit in which a man wakes up and wonders if he’s the butterfly he just dreamt — flits over the present crisis, as over a nightmare: