The Apple Merchant of Babylon 1

Genesis

🍎

The Genealogy of Mortals

Moses was a skinny man, nervous and unpredictable. He didn’t have big bones or big muscles. He was the type you’d find in a library, and not on some desert trek, with camels or dirt. He had a small, narrow nose, and piercing, icy blue eyes.

His grandparents Adima and Sheejee lived in the ancient city of Ur, yet they came from somewhere else. All Moses knew for sure was that they had always been dirt poor and that they always followed the male line. Whatever the women had done, after three generations, was a complete mystery. His grandmother Sheejee told stories about mountain valleys and misty lands beyond the Eastern Desert, yet these were overwritten by Adima’s stories about savannah south of the Nile, wicked pharaohs, and evil gods with hyena faces.

Most of Adima’s recollections of the cities he had travelled through were not complimentary. Horrible beasts flew in the skies and dire warnings were everywhere.

Adima’s take on their family history was that they were poor but noble, ever-respectful of the law, and favoured by Yahweh, the God in the highest Heaven. Horrible beasts may attack the cities of unspeakable evil, evil councillors may tax the poor to the bone, and evil rich men may take advantage of every slave girl in their possession, yet God would ultimately smite these cities and justice would prevail. Adima’s version of genealogy also included a midnight escape with the help of a washer-woman, a perilous voyage across a desert, several miraculous revelations, a long journey across water in the pouring rain, and the promise of a new land for the extended family.

On the wall of their wattle home in the slums of Ur, Moe’s grandparents painted a scene which explained their view on life. They were the dry sticks on a sacrificial pyre. They were the ashes that rose from the flames. In the end, they offered themselves to the sky.

When Adima and Sheejee were too old to work, their son Yaakov brought the whole clan north-west to Babylon, which for millennia had been a crossroads for all kinds of tribes and peoples.

In Babylon, Yaakov met a sweeper-woman of exceptional beauty. Her name was Zikirta, and her family history was a mythic one: apparently some of her ancestors fought an epic battle between Good and Evil. Evil was finally defeated by the Son of Light, who then built a golden bridge to a Better World. Yaakov and Zikirta both believed in the theme of suffering and of escape from this world to some better place. This belief helped them through their early years, when they were scratching a living doing odd jobs and selling castaway fruit and vegetables on the outskirts of Babylon.

Yaakov and Zakirta decided that it didn’t matter where they came from or what their religions said, as long as their belief in a better future and a Higher Truth helped them to survive. Zakirta said that they were living in a New Age, and as a result they needed a New Age philosophy. While their families may have worshipped different gods, hadn’t they been worshipping the same God all along? We’re all children of God, they’d say, although which God they never said. Their last word on the subject was, There is only one God.

As Moses’ parents moved up in the world, they bought a house five minutes walk from the centre of town. It had an old storeroom that Yaakov cleaned out and filled with shelves of tablets. The family library grew year by year. Eventually it contained every famous story written in the last two thousand years. They had the seven canonical versions of Gilgamesh, all fifty volumes of The Epic of Shamash, as well as all sorts of odd stories from Egypt about cat people and alligators that could talk, which gave Moses the creeps.

Moses loved nothing more than reading stories and then inventing alternate endings. He did this day and night, until finally Zikirta told him to get a job. “At least get out of the library and help your father in the store. Pomegranates don’t sell themselves you know!”

🍎

Free Trade

Moe learned to like doing business in the shop out front. It gave him a chance to meet all sorts of people and swap stories about the world around them. The only thing that bothered him was that there were very few ethical guidelines, and whenever they agreed on an ethical guideline no one followed it.

Moe figured it was the fault of the Indian fruit dealer Shesha. Ever since he brought in Kashmiri apples, people stopped buying the local fruit. They were frustratingly delicious. They were even better, Moe feared, than the ones from his family orchard on the outskirts of town. Moe tried to rally his family against the Indian, but all his family cared about was profit. They just wanted to make deals. And Shesha was the man for that.

Moe felt the same lack of interest when he talked to them about Yahweh. He repeated the old mantra about their God being better than all the others. It was a God who was above all the other gods, and who would unite everyone once and for all. But they just nodded their heads and said, OK, whatever. The only one who'd listen to him was Abe, and that was because Moe was his favourite nephew. With everyone else, it was profit over prophecy. They were deaf as doorknobs to his protectionist arguments and to the roar of his omnipotent God.

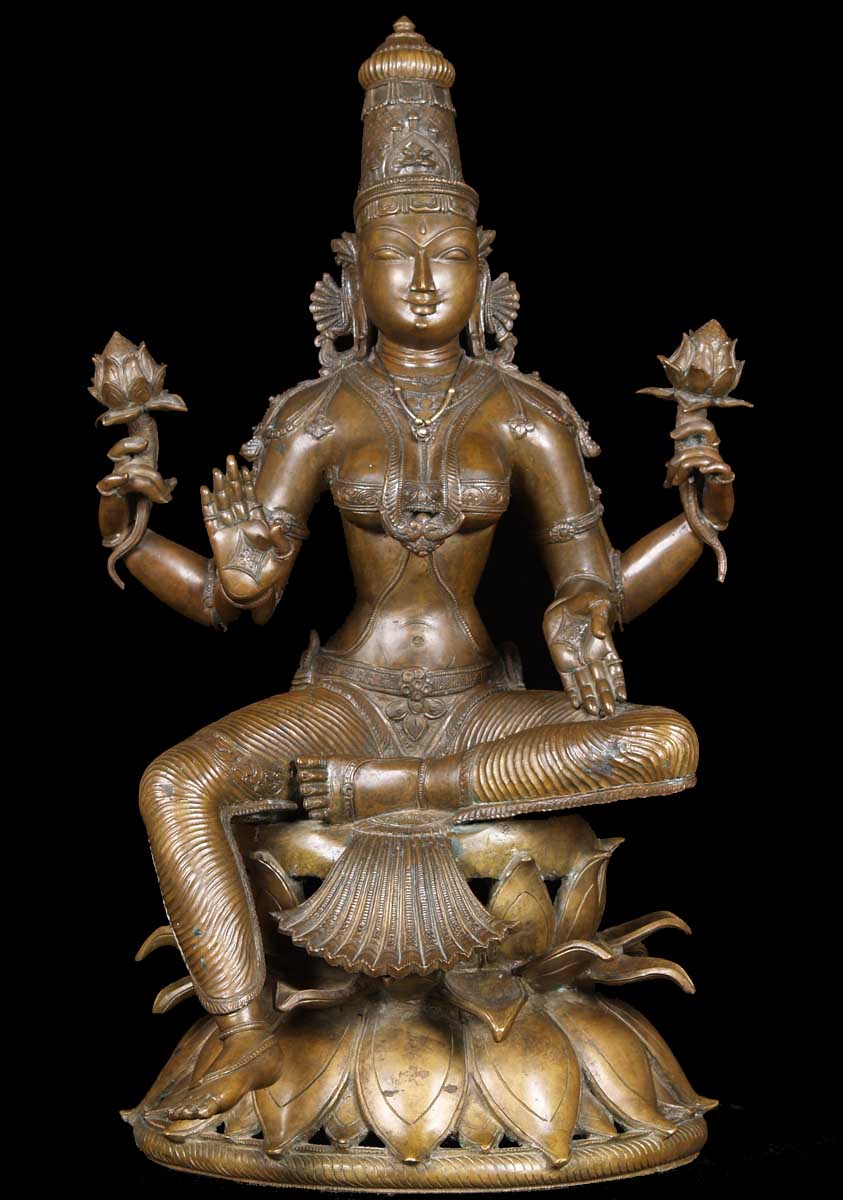

To make matters worse, everything Indian was the rage. Everyone in the market admired Shesha’s bas-relief of the goddess of Fortune. She had large breasts and spun something that looked like an apple on her finger, while happy elephants munched exotic fruit.

Moe's cousin Qayin traded his bronze six-pointed star, the symbol of their God, for a fancy iron image of the goddess of Fortune. Iron was all the rage. No one valued the old traditions anymore. It didn't help that the goddess had big round breasts, and that his God didn’t have any breasts at all. Yahweh didn’t even have a handsome face, or strong smooth hands. In fact, He had no body parts at all. Even worse, the goddess wasn't afraid to act like a flood-plain girl when some of the other gods came around. She multiplied shekels like children.

🍎

Olive Branches & Holy Mountains

Beneath his shop sign, Moe put up a small statue of a god meditating on the peak of a mountain. He made this compromise with the gods of India in the hope that the god’s asceticism, his deep breathing among icy peaks, would cool the avarice that possessed his fellow merchants. It should be noted however that Moe placed Yahweh’s six-pointed star above the god, just to make clear who was above who.

Moe made a further ecumenical gesture by writing some complimentary things about the Indian gods in his weekly journal of culture and religion, The Holy Mountain. He surprised his uncle Abe when he claimed that there were similarities between the older, more elegant Babylonian religion and the ingénue cults from India. Moe reminded his learned readers that according to Sumerian and Akkadian records, humanity descended from the mountain on which Utnapishtim’s boat landed after the Great Flood. He noted that Utnapishtim was warned to build his boat by Ea, the god of sweet waters. Likewise, according to Indian accounts, humanity descended from Manu, after Vishnu warned him of the coming Flood. Logically, there couldn't be two first humanities, so Moe concluded that the mountain must be the same mountain.

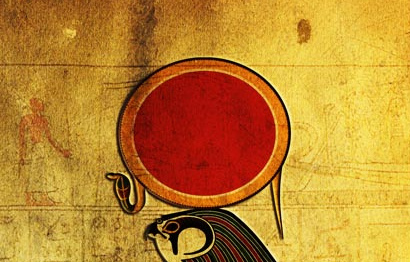

Intoxicated by the spirit of ecumenicalism, Moe reached out even further, to the land he always imagined as his own: Egypt. He knew that Akhenaten had tried to make the sun god the only god. Wasn't this what he wanted for his family's own tribe: a One True God? Moe chiselled a perfect circle at the top of a new tablet. Beneath the image of the sun-god, he made an outline of two columns, one in Babylonian cuneiform and the other in the new 'Aleph-Bet' script used by the Phoenician traders. In the two columns he wrote the following poem:

Ra

You who are always beyond our reach,

You who are sixty times sixty times sixty cubits from the earth,

Yet still we cannot look you in the eye.

You who are the origin of all life,

Who created man from the compassion of your tears.

Why look further for an image of God

Than this perfect circle of blinding light

Lighting the world in Its spinning flight?

Moe hoped that one day this poem would be read by children all over the civilized world. Perhaps his dual-script version would even help them to read the simpler Aleph-bet script that was now so snobbishly seen as only fit for workers and merchants. Wasn't he a merchant? Maybe if the other merchants could see that there was only one God, and that He was unattainable and that it was impossible to even look at Him (like the Sun) then they would stop all their religious quarrelling and favouritism, and get back to business.

Yet instead of prompting the merchants to think of higher things and of the common economic good, his discussion of Amun-Ra and the Holy Mountain only encouraged the shop sellers to import more pagan statues.

With the extra cash, the Persian middlemen bought more apple carts. The markets were soon glistening with the shiny russet spheres of Kashmir and Susa!

This was the last time Moe would ever compromise with the evil deities of a foreign land.

🍎

Eastern Gods

As if to mock him, Shesha put up a new image of a phallic god on the sidewalk in front of his shop. The young girls just stared at it. Shesha explained to them that the phallus was a pillar between Heaven and Earth, and that some of these pillars were wider than Marduk's beard. Soon there was a line-up in front of Shesha's shop, and people started disappearing behind a blue curtain at the back. Hours later they slank out of the shop, the tips of their hats touching their noses.

Shesha became downright arrogant, mocking the claims Moe made in his recent article The Boat on the Hill. Shesha scoffed at puny hills like Sinai. He pointed out that even Moe's beloved Ararat was nothing compared to Chhogori, which itself was nothing compared to the great Mother Goddess of them all, Chomolungma. And yet one week Shesha called his God Rudra and the next week he called Him Vishnu, and then the next week he said they were all called Brahman. It seemed to Moe that Shesha wanted his God to have his cake and eat it too. Not only was He transcendent and above everybody else, but He was also a fiery stud. Shesha’s new statue portrayed Him with his arm cupped around the torso of His consort, His middle finger just barely touching her nipple.

Moe’s customers crossed the street in droves. Then, adding insult to injury, Shesha put up an enormous image of a snake-god hovering over Vishnu, with his sexy consort at his side.

He then painted the breasts of the consort red, with little flecks of gold, just the colour of the apples that were right next to the statue and the sign, Two shekels a basket. Come in for a bite!

Below it Shesha carved into the grey stone several catchy verses extolling the powers of the snake. These lines had been sung to him by his grandmother over his bed from the time he was an infant to his twelfth birthday, at which time he left Jhukar to join his rich uncle in the plundered city of Mohenjodaro. It was there he met Dhargda, his Dravidian beauty. What did it matter if she was dark as Kali’s nipple, that she wasn’t high-born, and that she didn’t know how to do puja in front of Lord Vishnu?

Karshnaz, the Persian merchant next door, was not to be outdone by this brazen display of Indian mythology. He immediately imported an even larger statue of a fertility god, with a giant penis standing erect, bolting the Earth to the Sky. His brother Zardosht (or Zarathustra in his native Avestan language) found this a rather vulgar display, and decided to lend the place a dash of class by putting up a panel of dancing apsaras.

Moe shouted to the sky: Fornicating nymphs and stone idols! Is there no end to their avaricious depravity? Moe even suspected that they were lesbian apsaras, as corrupt as the wicked men he had seen fondling each other in the backstreets of Sidamu.

What had all his attempts at cross-cultural mythology come to? Thinking back to his article in The Holy Mountain, he began to see that the Mesopotamian mountains and the Indian mountains weren’t the same at all. It was all a sham, this good will and reaching out to foreigners!

The final straw came when Zardosht bought an enormous stone image which was half-man and half-woman.

Moe was beside himself with indignity: And now they’re bringing in transexual idols! What next, transexuals marrying transexuals?

Moe couldn't keep track of the strange types that went through the blue curtain after that.

Enraged, he went to the front of his shop and tore down the statue of the meditating god on the icy peaks. With his chisel he flattened the inscription on the grey stone. In its place, he chiselled in deep and angry grooves: Climb your own mountain, Zarathustra! And take your apples tarts with you!

🍎

Next: Apple Merchant 2: Begin at the Beginning