The Three Graces 💚 Palermo

Pietro Parlante

Pietro Parlante spent seven months searching for a precious green ore in Uzbekistan, digging and blasting near the site of the famous geologist Paulo Lazuli. By chance, Pietro hit upon an enormous strata of ceramic shards and stone artefacts. These turned out to be remnants of a small settlement on the Silk Road. The town, translated Monkey Business, began trading around 2200 BC and was destroyed by the Mongols in 1227 AD.

The artefacts contained proof of continuous trade between the Middle East and China for 3000 years. This lead to the revelation that everything the Chinese were supposed to have invented had in fact come from the Persians and Babylonians. Paper, noodles, clocks, the abacus — the greatest inventions of China were in fact cheap knocks-offs.

Chinese historians could barely suppress their anger. Only with great reluctance did they allude to Pietro’s discovery — and even then, only in coded notes at the bottom of their annotated bibliographies. They were careful to place his name in the middle of long final entries, under headings such as Xenolithic Obscurities and ZrSiO4 & Four Other Old Ideas.

Two meters below Monkey Business, Pietro rejoined a slim trail of bright green flecks, interspersed with silver and crystal striations. The slim trail widened, plunging deep into the ground. Pietro had discovered a rich vein of mystocryptic ore. Where had he seen that before, that same combination of silver and crystal striations?

Five seconds later, he knew the answer. Immediately, he left the camp, without even wondering who would fight over his discovery. Would the Russians do another Ukraine, this time claiming that the Uzbekis were in fact Cossacks and therefore part of the Russian Empire? Would the Turks make eastern advances and assert an undying love for their Turkic brethren? Or would the Chinese or Americans buy off the politicians first? Pietro couldn’t care less, and just drove to Samarkand Airport.

He took the first flight to Dubai, London, and Edmonton, without so much as a night in a hotel. From the Edmonton Airport he drove directly north to a river bed he knew very well. Jumping out of the truck he drove his shovel into the ground which was glowing with silver and green. After ten straight hours of digging, he discovered the richest vein of mystocryptic ore the world has ever seen. 75 billion metric tonnes of the stuff. One week later Pietro returned to Palermo with a monthly stipend of ten million euros.

The reason that mystocryptic ore was so valuable was that it was composed of a unique multidimensional latticework that can process 256 million algebraic curves simultaneously. The calculations made possible with silicon and germanium processors look like calculations made on an abacus — which, Pietro pointed out was invented in Sumer five thousand years ago, and was only manufactured in Chang’an sweatshops for the last two thousand years. He added, And donta talka to mee abouta za pasta!

💚

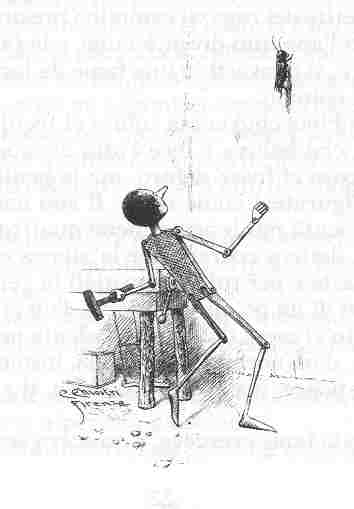

The first thing Pietro did with the money was rescue Grillo, his crotchety father, from his meaningless job at Geppetto Corp. According to Grillo, working conditions at the woodworking factory were far worse than in a Wushan sweatshop. Grillo forbade his son to even make a comparison in that direction.

Raising his index finger and clenching in the other hand a monthly report, Grillo shouted that managers like him were continually pressured by upper level managers, who knew nothing about the laziness of the Sicilian factory worker. The upper level managers were themselves pressured to increase production by talking corporate heads in Palermo. These, in turn, bobbed and jerked at the behest of mafia dons in Naples and Rome. Somewhere at the very top was Mangiafuoco, the Fire-Eater himself. The hierarchy looked something like this:

Grillo's dull blue eyes bulged from his face (and took slightly different trajectories) every time he looked into the eyes of the cross-eyed lackey named Stupendo, who had the same blue eyes, a mass of frothy orange hair (mostly on his eyebrows), and a luminescent lime forehead. Stupendo had lost both his arms in two different lathe accidents — both times because he couldn't tell the difference between the on and the off switch. To Grillo's disbelief, not only did the union defend Stupendo; they made him Grillo's co-manager. This meant that Grillo had to explain every decision he made to Stupendo, who couldn't understand what was wrong with 75-minute breaks or looping electrical wires over bandsaws.

When Grillo left for work Monday morning, he looked calm, almost philosophical, like a Zen cricket contemplating Keats’ “Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, / Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; / Conspiring with him how to load and bless / With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run.” When he came home from work Friday evening, his whole head was twisted and his nose was upside down.

His left eye twirled into places so demented that only the tight red scarf around his neck could rescue him by cutting off the blood.

💚

To give his father some place where he could let off steam Friday nights, somewhere he could express his outrage among like-minded old men, Pietro set him up with an open tab at the local backstreet café, Il Doloroso Burattino. His mother knew the café doubled as a whorehouse, with dancing girls from Amsterdam, Córdoba, and Kiev. But she hoped the "slutty dancing puppets" would keep Grillo off her back. "Let the old geezer talk their heads off!"

As a precaution, Pietro removed all blunt instruments from his parent’s suite, just in case his mother was tempted to nail the old man’s head to the wall once he got home.

💚

Pietro’s quest for mystocryptic ore was part of a larger obsession with finding things that other people couldn’t find. This obsession was in turn part of an even larger obsession: he had to know more than anyone else. Especially more than his father, who professed to know everything.

Pietro was certain that he knew more than anyone in Palermo. He also felt that he knew more than anyone in the entire Mezzogiorno, from the dimwitted professors at the University of Naples to the lazy philosophers in the Greek cafés of Syracuse. Beyond the Mezzogiorno were idiots who couldn’t speak Italian properly. What they did or didn’t know was of little consequence. In any case, he knew more about what they pretended to know than they would ever know. Donald Rumsfeld once argued that in addition to known unknowns there were also unknown unknowns. Pietro didn’t believe that for an instant. He was smarter than Donald Rumsfeld any day.

His sister Francesca complained that Italians think they know everything, and that they always manage to find the words to say what they think. She said, They can't shut up, even for un minuto! Especially her boyfriend, who couldn’t stop talking about his new motorcycle. She yelled at her brother, Why doesn’t ee justa shuddup about it? You thinka you can find anything, Pietrino? Well, try to find even un Siciliano who canta find the words to say esattamente whata he wants to say. I dare you!

At first he thought she was joking. But she wasn’t. So he decided to prove her wrong. He knew more than she would ever know.

Francesca had one condition: he was forbidden to include Italians who wouldn’t say a word on grounds of their political ideology. This included government workers, bus drivers, train ticket sellers, and everyone else associated with a union. Pietro was undaunted. He was sure that out of sixty million Italians, he could find at least one non-unionized person who couldn’t find the words to say what was on his mind.

Francesca told him that it was ridiculous to even try. She then started talking, again, about how her boyfriend refused to listen to her. She said he never stopped talking about his big yellow Ducati, the one with the enormous engine and smooth clutch. He keeps telling me that I’d love it, if I just let him put it between my legs. I tried to tell him that I’d — but at this point Pietro saw the magnitude of his task. He abruptly excused himself, and, while Francesca added a further complication — He said he was even willing to stick a muffler on his exhaust pipe — Pietro slipped out the door. He said good day to the doorman and stepped out onto Via della Libertà.

💚

It wasn’t as easy as he imagined. Everywhere he looked, people were talking, articulating exactly what was on their mind. Try as he might, he was unable to find a single Italian who was at a loss for words. So he decided to attack the problem with the methodological rigour he reserved for geological exploration. He first canvassed the neighbourhood, accumulating facts and figures. To ensure accuracy, he conducted induced polarization surveys: he hammered iron stakes into the corners of cafés and measured the ratio of electrical charge to resistance in each room.

After making numerous calculations, he was despondent. It was a near statistical certainty that any given Italian was capable of saying exactly what was on their mind on any given occasion. He once heard a goatish, grey-bearded tourist complain to a pretty waitress, They just blab on and on, and it all sounds like gibberish! Pietro resented the charge of gibberish, yet the old goat was right about the on and on.

Yet it was only a near statistical certainty, not an absolute statistical certainty. He was damned if he couldn't find that one crucial exception. He could see it now: Francesca and the old goat commiserating arm in arm, tears dripping down their faces.

Pietro was determined to find, somewhere in Palermo, something even more rare than a vein of mystocryptic ore beneath the rugged hills of Tajikistan.

💚

Next: 💚 I, Claudia

Contents - Characters - Glossary: A-F∙G-Z - Maps - Storylines